Acteurs, temporalité et géographie des massacres

Massacres primarily attributed to Catholics?

These massacres, in French territory, were mostly committed by Catholics. It is not that the Huguenots refused the call to violence, but this rarely took the form of collective action against ordinary people of faith. It mostly targeted soldiers, clerics, and even objects. Considering holy images a form of idolatry, the Protestants favoured acts of iconoclasm[1] ; the first took place in France in 1528 and was followed by several waves, in 1555 in Toulouse, in 1561 once again in the capital, in many towns in 1562.....it was a feature already described by the Calvinist authors of L'Histoire Ecclésiatique, affirming that the 'religious' made war only on images and altars.

The Catholics attacked people, the Protestants, property. This rather complacent picture of Huguenot violence is only relative. Protestant mobs certainly did attack the ordinary faithful. The massacre of Michelade took place on the night of 30 September to 1 October 1567 in Nîmes – after St Michael's Day, hence the name – and it is undoubtedly the best known of the massacres committed by the Huguenots. The governor of the province imposed Catholic councillors on the town, which had a Protestant majority. Although the Huguenots took back control of the municipal institutions, a trivial incident between the two communities (a woman was jostled by one of the governor's soldiers) degenerated into a riot. Between 15 and 120 Catholics -civilians, religious and military leaders, were taken to the bishop's palace in Nîmes, stabbed to death and thrown into a well. On 15 August 1562, the killings at Lauzerte (now in Tarn-et-Garonne), where 94 clerics were murdered, is another massacre perpetrated by the Protestants. Conversely, Catholic violence was also aimed at property. Conflict led to the destruction of Protestant churches, and bibles in French were burned.

Informations[2]

Informations[2]All the same, historians from Natalie Zemon Davis to David El Kenz, including Denis Crouzet, have all confirmed that Catholics were the main perpetrators of massacres in the kingdom of France.

The location of massacres in time and space

The historian David El Kenz set out to quantify and locate massacres. Massacres are not random; on the contrary, they have characteristics which hold true not only for France in the wars of religion.

They happen in the areas where the two communities, Catholic and Protestant, are relatively demographically balanced.

They are a response to the rejection by the Catholic majority of coexistence and civil toleration[3]. After 1577 the frequency of massacres in towns declined as many Protestant communities had been forced to disperse and emigrate, such that those remaining did not pose a threat to the Catholic majority.

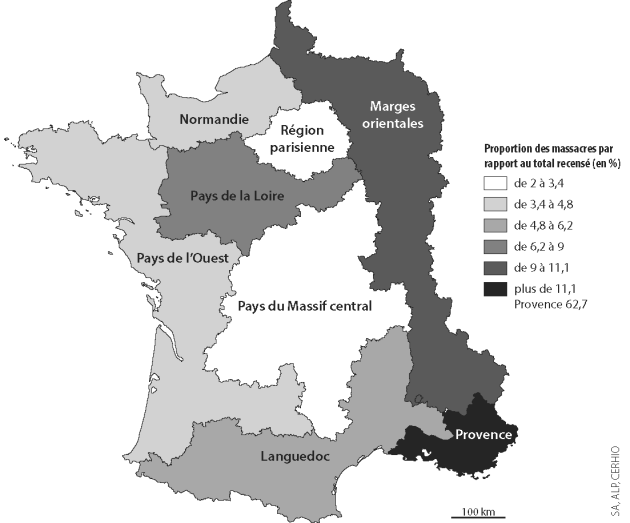

Many massacres were carried out alongside military action. According to the historian David El Kenz' analysis, between 1559 and 1571, out of a total of 58 massacres cited in L'Histoire des martyrs (1514) begun by Jean Crespin and continued by Simon Goulart, and in L'Histoire ecclésiastique des Eglises reformées au royaume de France (anonymous, but attributed to Théodore de Bèze[4] , 1580), the greatest number of killings took place in Provence (62.7%), followed at a fair distance by the Loire Valley (8.5%), Languedoc (5.2%), Champagne (4.6%), La Guyenne and Poitou (4.6%). This geography of killings corresponds to the areas where combat was most intense. David El Kenz shows that a third of massacres occurred when a town was taken. In Tours, for example, 200 Protestants were killed during the retaking of the town by the Catholics on 11 July 1562.

The net over-representation of the Midi in this geography of massacres appears in fact to be linked to the unusual urban density of that region; the forced were balanced, which favoured the escalation of violence. This bias is certainly also linked to the source; the Reformed churches of the Midi were especially dynamic and it was they who provided the author of L'Histoire ecclésiastique with the reports of the massacres. Conversely, there were no killings in Brittany, due to the fact that there were few Protestants there and the Catholic governor, the Duc d'Étampes[5] , acted with moderation and prevented fratricidal strife.

Informations[6]

Informations[6]