Introduction

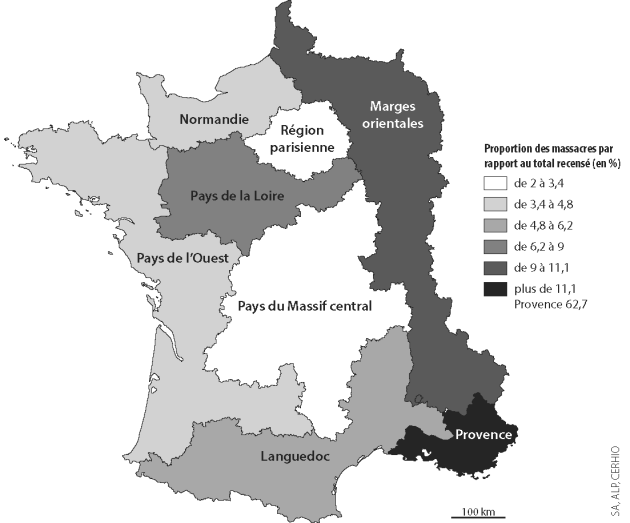

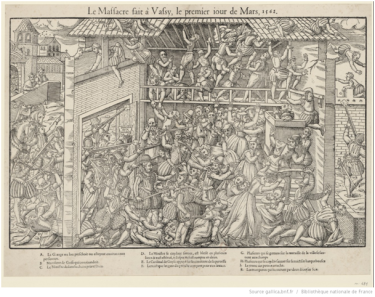

The eight wars of religion experienced by France between 1562 and 1598 were marked by many massacres. The first conflict was initiated by the massacre of dozens of Protestants in a barn in the town of Wassy in Champagne on 1 March 1562. The massacre of St Bartholomew[1] at the end of August 1572 and its extension to the provinces undoubtedly represents the zenith of this butchery, which tended to decline in the following years. Such incidents were not unique, either inside or outside Europe; massacres committed in the Russia of Ivan the Terrible (c1547-1584), massacres at the time of the conquest of Cyprus by the Ottomans (1571) and during the wars against Persia (1576-1592), as well as massacres in the Japan of Hidyoshi (1537-1595); the exception during this period was in Asia during the short reign of the Chinese emperor Longqing and that of the much longer reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar (c1556-1605), although he built his empire partly through force. The sack of Rome in 1527 and the conquest of the Aztecs by the conquistadores in the 1520s were accompanied by massacres which scandalised many observers and gave rise to lively denunciations. The massacre, though not something banal, was thus a feature of the mentality of the times and is often related to its biblical archetype, the massacre of the innocents[2] . Contemporary engravings such as those of Tortorel and Perrissin make implicit allusion to this.

Informations[3]

Informations[3]The civil wars of religion and the litany of cruelty and injustice which accompanied them are sometimes seen as crossing a new threshold of violence. The lexicon, moreover, is evidence of this. Even the term ‘massacre' in its contemporary sense is derived from a tract, Histoire memorable de la persecution et saccagement du people de Mérindol et a Cabrières, about the massacre of Vaudois[4] heretics in Provence . The term was originally associated with butchery, denoting the butcher's chopping block and the “massacre”, the knife. The term was used above all by Protestants describing Catholic violence and its use expanded markedly after St Bartholomew's Day, in France and abroad. From the end of the sixteenth century, the English commonly described this event as the “bloody massacre of Paris.” The semantics surrounding the word 'massacre' are always carefully selected in tracts and are employed to discredit an adversary; by 'massacre', these texts evoke cruelty, persecution and barbarism, a massacre as opposed to ordered violence and the chivalric code of honour used in war.

What is understood by 'massacre' here? According to the political theorist Jacques Sémelin, it can be defined as “a form of collective action aiming to destroy non combatants, generally civilians.” The massacre is not aimed at defeating the enemy, but at destroying its essence. While the massacre appears frenzied, irrational, it is based on a relatively logical intent and is sometimes a response to strategic imperatives.

Informations[5]

Informations[5]