The burden of age-old religious practices

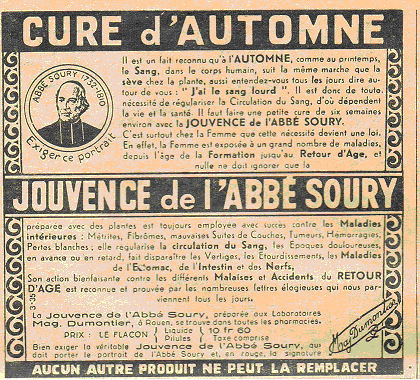

At the time of the Ancien Regime it seems difficult to draw the line between the medical and the religious dimensions of care. Disease was often considered the result of sin or a message calling folks to conversion. An hospital was a charitable rather than a therapeutic environment. The populations massively turned to healing saints whilst a very significant economy of ecclesiastical remedies thrived. The concoction of Jouvence de l'abbé Soury, a herbal remedy acting against blood circulation problems devised mid 18th Century by a Rouen cannon was developed by a chemist in the following century to such acclaim as to be marketed still in the 21st. General practitioners were not many (2500 shortly before the French Revolution, as against the 25000 French surgeons active in the same period) and frequently found themselves at the priest's beck and call, notably when they attended to the dying, and they had to compose daily with ubiquitous nuns.

The second half the 18th century witnessed the emergence in Western Europe of a new medical model founded in clinical and anatomic observation that gradually transformed body representations and healthcare practice. The medical visit at the patient's bedside betokened the advent of a hospital intended as a “healing machine”. In period engravings the nun's wimples is seen centre stage between the medical staff and the patients in their beds.

The consulate and 1st Empire set the legal basis of healthcare professionalization for a century whilst the medical profession took shape under the Louis-Philippe's July Monarchy[2] (there would be 18000 practitioners in 1847), even though its image remained loathsome in French society. In fact, ethical recommendations circulating in the profession at the time concerned essentially commercial good practice. Therapeutic advances hardly matched the progress of professionalization. The Catholic Church was happy to settle for expectant care[3], which privileged observation over intervention, reserving its censure for materialist theories such as phrenology[4]. In this first phase of 19th century, the priest and the nun still held on to an undisputed healing role wherein spiritual input was an acknowledged element of a still influent vitalism[5].