The secularization of Paris' hospitals at the end of the 19th century

From the 1870s onwards, freethinking and anti-clerical actors became a powerful voice on Paris' municipal council, which subsidized its public hospital system; partly goaded by active Catholic proselytism in Parisian hospitals, they campaigned for the secularization of the city's health care establishments. Specifically they demanded the termination of hospital chaplaincies that had proliferated during the Second Empire, and the exclusion of the nuns who, since the beginning of the 19th century dominated French hospitals' internal services. The process unfolded just over a generation, that is in a short lapse of time.

1878 | The nuns leave Laënec |

1880 | Dismissal of some ten chaplains in most large hospitals that had several incumbents (Salpêtrière, Saint Louis, Lariboisière, La Charité, Incurables, Bicêtre, Ménages); suppression of Sainte-Anne's chaplaincy; the nuns leave La Pitié. |

1881 | Suppression of chaplaincies in small care homes, at Tenon and Saint-Antoine. The nuns leave two care homes: La Rochefoucauld, Petits-Ménages and Saint-Antoine |

1882 | The nuns leave Tenon and Lourcine |

1883 | Suppression of the chaplaincy services baring a few hospitals linked to a religious foundation |

1885 | The nuns leave Incurables and Cochin |

1886 | The nuns leave Enfants-assistés, Necker, Enfants-malades |

1887 | The nuns leave Lariboisière, Trousseau, Beaujon |

1888 | The nuns leave La Charité |

1892 | The nuns leave Berck where the chaplaincy is also abolished |

1908 | The nuns leave Hôtel-Dieu and Saint-Louis |

H. Guillemain, « L'hôpital et ses religions. Pratiques conflictuelles dans les établissements de l'Assistance publique (1870-1914) », in F. Pitou et J. Sainclivier (dir.), Les affrontements. Usages, discours, rituels, PUR, 2008, p. 146-158 (translation by the translator of the course) | |

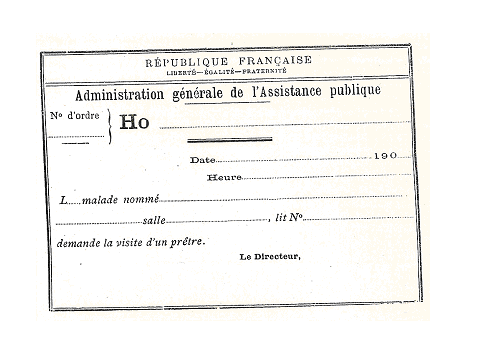

Thereafter, the Paris chaplain may no longer reside in the hospital, he was no longer salaried but compensated according to religious services performed. He may no longer visit the wards but at a patient's express request and with a doctor's permission. The conflict between Paris' local authority and the chaplains then veered on the matter of sacraments. In order to keep this practice under control, the administration produced a counterfoil book a slip of which was to be filled with the date, time, patient's bed number and the manager's signature and handed over to the priest in order for him to be admitted into the ward. Two approaches to the “administration “ of sacraments were confronting each other. The republican motto toping each chit spelt out the secular nature of the exercise, which duly observed – not a universal occurrence – de facto drove down religious practice. These conflicts were party to the redefinition of the symbolic realms occupied by medicine and religion. Meanwhile religious processions were banished from hospital precincts and were refocused on the chapel, and the naming of wards was revised: the names of doctors and Enlightenments philosophers replaced those of saints.

Significant thought it was, this episode is misleading and does not lend itself to generalisation. This Parisian confrontational situation should not detract from the reality of a globally uneventful secularisation. From the Napoleonic era onwards, confessional staffing never ceased growing, frequently to the detriment of lay employees. In 1914, French hospitals were staffed at 40% by nuns. In some areas such as the Eastern Massif Central they held a quasi monopoly. In clinics, rural and working class communities they often substituted for largely absent physicians. A stable and disciplined personnel (readily accepting of asepsy[1] rules for instance) the nuns boasted well-acknowledged technical competence. They proved a vector of medicalization easing the patients away from self-medication[2] and towards entrusting their health to a third party. Some disciplines overlooked by the State became the preserve of religious specialists such as the care of the insane taken over by the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God[3]. The end of the 19th century was marked by a diversification of this caring activity through the creation of orders dispensing care in the home or the foundation of private faith hospitals.