Emblematic confrontations in the last decades of the 19th century

The emergence of a radical republican fringe came to add a political dimension to existing tensions between medical science and religion – the more so when Christian paranormal found novel outlets in times of millennialist restlessness caused by the return of the Republic. Désiré-Magloire Bourneville[1], a physician committed to the education of the mentally retarded and founder of militant medical publications, made it his business to expose the mystical deception of stigmatics become the Catholics and Monarchists' mouthpiece. His book Science et miracle. Louise Lateau[2] ou la stigmatisée belge (Science and Miracle. Louise Lateau or the Belgian Stigmatic 1878) turned him into one of the champions of this anticlerical and anti-faith medical trend.

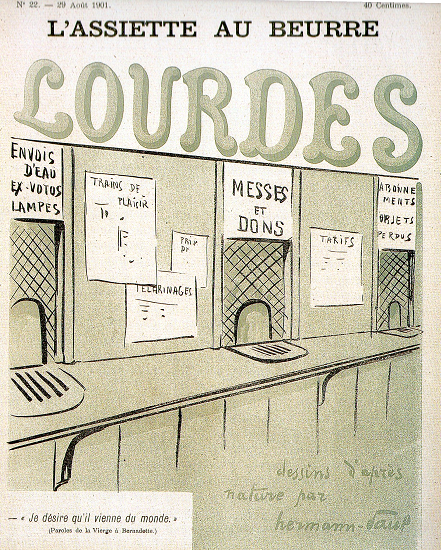

Scientific research increasingly investigated beliefs, especially in the new field of neuropsychiatry. The climax of this political and medical critique hinged on the development of the sanctuary at Lourdes, a place of mass cures underpinned by ultimate modernity: the press and the railway. In the small Pyrenean town, the Catholic Church recognised the Virgin Mary's apparitions to a young shepherd girl, Bernadette Soubirous in 1858. Some 12 years later, the Assumptionists[3] had masterminded the Catholic faithful's visits to the cave at Massabielle. They set up a national pilgrimage and broadcasted Lourdes' image to the world via their magazine Le Pélerin, created in 1873. Faced with this unabashed Catholic miracle drive, some physicians sought to have the pools, where sick and healthy were indiscriminately immersed, closed on grounds of barefaced disregard for hygienist precepts. Meanwhile neuropsychiatrists blamed psychosomatic pseudo-cures on hysteria[4]. In the anticlerical press arguments and imagery colluded to reject what was described as a new temple of credulity and easy money.

“it is my wish that people came”

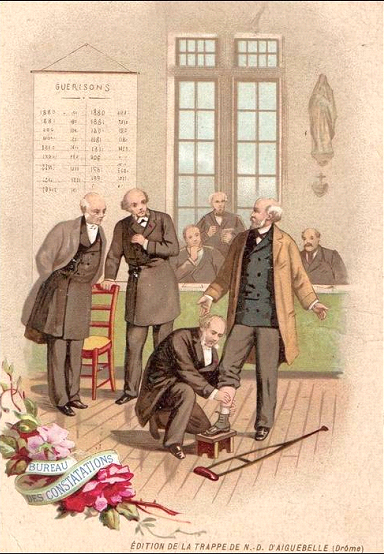

But at the core of this symbolic confrontation a complex situation has to be disentangled. To start with, the Catholic Church is very wary of popular mystical demonstrations and has at its command a long-held procedure devised to sort what it terms “supernatural” from deception. In this configuration the scientific argument had a major part to play. Lourdes' sanctuary was soon the scene of the internal development of a Catholic medical organisation, benefitting in 1884 from the Société médicale Saint Luc, Saint Côme et Saint Damien[6]. The latter adopting first the model of the learned society would swing into full fronted Catholic action. Its research soon focussed on medical issues controversial at the end of the century: death, obstetrics, artificial insemination, anaesthesia, hypnosis. The Medical Bureau was the Catholic medical response to criticism of the sanctuary as much as a modern extension of the existing method of enquiry into the validation or otherwise of such and such a “miracle”. When in 1906, the sanctuary's pools were threatened with closure by hygienists, the Société de Saint Luc was at the forefront of the campaign to oppose it in medical circles, calling for a referendum. Behind the outward conflict between medicine and religion, this evolution marked a mode of medicalization of the clerical argument and of the Lourdes sanctuary.

In 1894, Léon Daudet published Les Morticoles. Yet to become a leading luminary of the far-right Action Française, he concluded his medical studies with this anti-medical bombshell that caused an uproar. Catholic, anti-republican and Anti-Semitic, the author attacked with equal ferocity contemporary physicians' materialism and hygienist imperialism. A few years later Joris Karl Huysmans, a novelist and Catholic convert produced in a similar vein an apologetics of the miracles performed in Lourdes. Though medicalization had undeniably progressed in every strata of French society at the end of the 19th century – and with the notable support of Catholic practitioners and institutions active in new fields (e.g. fighting tuberculosis and cancer) – it still met with resistance that could be nurtured by a particular brand of Christianity. So that, in the 20th century, without the benefit of a straightforwardly resolved conflict between religion and medicine, its enduring existence still has to be reckoned with in the finer points of any polemic.