Fresh grounds of confrontation

In the second half of the 19th century new conditions had come together to bring about an ideological medico-religious showdown. General practitioners had reached a superior social status and acceded to political responsibilities, which enabled them to influence major societal reforms. Experimental medicine[1] unequivocally advocated the detachment from metaphysical causes whilst hygienist medicine scored hitherto unhoped-for results. At that same time, however, clericalism reached a peak as demonstrations of popular devotion found many and manifold outlets. Those religious and medical dynamics were set on collision course as soon as the advent of new medical techniques, such as the Caesar section[2] forced the church to take a stand. This confrontation did not however oppose two discrete social groups: both clerical and medical circles were internally divided by the dissemination of these techniques.

The case of the fight against pain, which had not hitherto been a priority, is a prime example of the complexity of the relations between medicine and religion. Still holding sway was the conception of protective pain, the sign of a responsive vital force. To physicians, pain served as a diagnosis, thus it must not be lessened. Indeed, causing a greater pain could be advocated in order to push the original one out of mind (say by using moxa sticks[3]). This medical understanding of valuable pain reinforced the Christian concept of suffering as redemptive and a desirable method of perfection. However, in the middle of the 19th century, techniques became widespread which brought these attitudes into question.

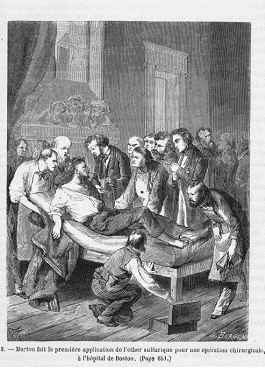

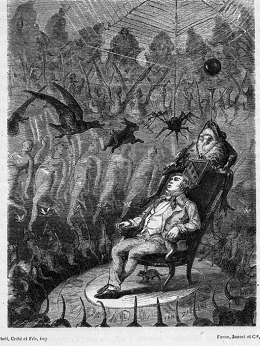

Ether then morphine[4] would henceforward offer the possibility to operate under anaesthetics and to kerb the most intense suffering. The two engravings from Louis Figuier[5]'s book Les Merveilles De La Science, Ou Description Populaire Des Inventions Modernes (The wonders of science or a popular description of modern inventions - 1891) show the two sides of this invention. The hope aroused by American dentist William Thomas Green Morton[6]'s experiments in the 1840s, as well as the irrational fears the loss of their consciousness would inspire in people 20 years later. This dread triggered reactions in the Catholic Church for whom the subject's free will is prerequisite to moral existence. The actors' conversion to these techniques was not immediate and frequently implemented under pressure from their affected patients (more alert to their bodily sensations) and further advanced by the weakening of Christian fondness for pain and medical vitalism.

The debate was no less intense in medical and religious circles when it came to redefining a “good death”. Whilst debates about euthanasia were still peripheral, doctors sought to arrive at a precise physiology of death that brought about questioning about the proper time to perform the last rites. The occurrence of suicide widely publicised during the July Monarchy also stirred up fresh conflicts. In the absence of any legal sanction (abolished during the Revolution), clerks and medics found themselves on the front line. The former helped causing a surfeit of denied burials in consecrated ground. The latter sought on the contrary to exculpate suicide by stressing its pathological dimension connoted, notably, with melancholy. In fact the confrontation was not so clear-cut. Faced with this perceived “suicidal surge” everybody pondered means to curtail the phenomenon: while physicians envisaged the handing over of suicides' bodies for dissection in medical amphitheatres for punitive purposes, the Catholic Church on the other hand, fell back on medical arguments for its casuistry: “« Burial rites cannot be denied those who kill themselves in a frenzy or other extreme illness, or when demented. »

”