Le christianisme, religion de martyrs depuis les origines

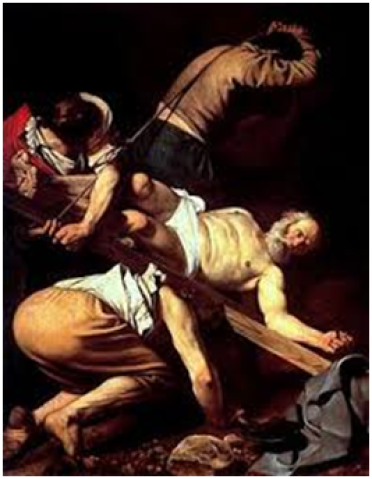

The Christian religion is founded on the experience and celebration of martyrdom through the passion and crucifixion of Christ. His self-sacrifice is its founding raison d'être. This principal message was promulgated by the founding fathers of Christianity and, indeed, many chose to imitate Christ and also to die as martyrs to the (true) faith. The apostles Peter (who was crucified), and Paul (who was decapitated), are two famous examples, especially because their fate inspired many artists [1]. The apostles and other original witnesses and disciples were added to by many Christian martyrs up to the third century during successive waves of persecution in the four corners of the Roman Empire. The commemoration of their exemplary deaths through cults centred on their real or supposed burial places, or their real or supposed relics, is the departure point for the veneration of saints.

Informations[2]

Informations[2]In effect, the first saints who were recognised as such by the ‘vox populi' and then by the Church, were all martyrs. There is a large number for the simple reason that the death of a martyr, for the first Christian communities, was considered as the noblest form of witness of the Faith and defence of the truth. For martyrdom to be effective, it must be consented to without being suicide. Most of all, it is essential that the motive is principally and clearly identifiable as religious. On these criteria depends the admission of Christian martyrs to the ‘martyrologies', lists of saints recognised by the Church as worthy of veneration. There were many revisions to these until the fixing, by order of Pope Gregory XIII[3] , of a ‘Roman martyrology' in 1583.

This compilation, also called a ‘panegyric', has been revised many times; gradually as the procedures for canonisation have become more complex and formalised, the ecclesiastical authorities have added new saints and deleted others, notably many of the ancient martyrs. The most recent significant purge was carried out rather discreetly in the years following the Vatican II Council, a period during which there was a marked attempt to distil practices, amongst others, in the area of the cult of saints. Certain sainted martyrs, such as Laurence[4], have been venerated for many centuries. Their tragic story forms part of the collective imagination, due amongst other things to the artistic representations they have inspired [5]. Many other martyrs still have their place in the ‘Roman martyrology' but are no longer the object of public devotion. This has happened to Polycarp[6], one of the first martyrs whose fate is well documented, thanks to an account given by eye-witnesses towards the middle of the second century .

Informations[7]

Informations[7]While persecution dried up in the period when Christianity became an accepted religion, and then the religion of the State, a second category of saint, that of ‘confessors' who bore witness to Christ without sacrificing their lives for Him, was added to that of the sainted martyrs. But that of the martyrs, considered to be particularly powerful intercessors, are still fully present in the Catholic martyrology, especially since more recent persecutions have added new names to venerate. Amongst those who joined the ranks of the saints of the Catholic Church at the end of the twentieth century are Edith Stein[8] and Maximillian Kolbe[9] , killed in the Nazi concentration camps.

In addition to these are the ‘martyrs of Brazil' and the ‘martyrs of Japan' of the sixteenth century, the ‘martyrs of Paraguay' of the seventeenth century, the ‘martyrs of the (French) revolution', as well as the ‘martyrs of Vietnam', the ‘martyrs of Korea', and the ‘martyrs of Uganda' of the twentieth century.

In parallel to the theological discourse on martyrdom there has developed a significant literature of hagiography which has flourished since the writings of the Church Fathers[10] , and reached its apogee in the middle ages, in the Baroque era, and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In Jacques de Voragine's[11] Golden Legend, the most celebrated flowering of this tradition, produced in the middle of the thirteenth century and widely read throughout Latin Christendom, the sainted martyrs are over-represented. . This is also generally true of the devotional books encouraging the veneration of the saints in the modern and contemporary era. Certain metaphors devised for the martyrs of early Christianity, such as blood as the seed of the Church, are reproduced and developed in writings (apologias) in defence of Christianity.

Hagiographies create and perpetuate the ‘spirituality of the martyr', seen as an authentic ‘martyr mystique', amongst other things through its close association with the principles of aestheticism. They emphasise the primacy of the spirit over the body; the Christian should endure physical suffering, which allows them to be raised to a new, purely spiritual level of existence and to bear witness to the truth of the Faith before the world. The metaphorical use of the theme of martyrdom is evoked, for example, in the trials of monastic life; religious people do not die as martyrs but suffer privations like the martyr. The simple ‘desire to be a martyr', even if it is not enacted, is a sign of sanctity, often evoked in the lives of confessor saints (especially female). It is also a path to spirituality for all Christians who desire to follow, at least symbolically, the example of Christ and the sainted martyrs. This exaltation of the ‘martyr for love' is particularly developed in the female mystic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an era of religious schism and war, was incontestably a second ‘golden age' of martyrdom, after the first ‘golden age' of the third and fourth centuries. The followers of all the Christian denominations in conflict – Catholics, Lutherans, Reformers, Puritans, Anabaptists and others, sacrificed themselves for the ‘true faith' and, despite themselves, became victims of repressive measures or complicit in them. The very numerous ‘martyrs' created by confessional conflict in the modern era were evidently not all saints according to the criteria defined by Rome. The term ‘martyr' took on a broader meaning in the context of the wars of religion, notably (but not uniquely), from the pen of Protestant authors . To their own side, all those who die for their faith under religious persecution from an ‘impious' state or by other enemies, are martyrs. Thus there are Protestant martyrs in Catholic held territory, Catholic martyrs in Protestant held territory, and Anabaptist, spiritualist and antitrinitarian martyrs all over.

Like massacres and iconoclasm, with which it is closely associated, martyrdom may be considered as a form of violence typical of wars of religion; of these conflicts, like civil and fratricidal wars, overlaid with eschatological considerations and apocalyptic terrors. The works of Denis Crouzet on the ‘God's warriors' have been the object of a great deal of criticism by historians who suggest they exaggerate religious factors. This does not prevent other authors, above all David El Kenz, emphasising, rightly, the symbolic and ideological power of martyrdom. The violence inflicted upon martyred bodies is much more than the violence of war; it is redemptive for the person and the group they belong to. It also carries a message of the world turned upside down and the approach of the end of times. This view may be found in many discussions of martyrdom to this day.