Images of living things within a Muslim context: distinguishing between facts and norms

The chief elements of an art labelled as “Muslim” or “Islamic” are floral or geometric patterns, plus calligraphy. They are very present in the architecture, which embraces other minor arts and crafts such as arabesque, woodcarving, decorative metalwork, plasterwork, stained glass and more. To this abstract ornamentation, we should add figurative themes. Islamic art is closely linked to space, favouring interior rather than exterior environments. This is evidenced in mosques and madrasas, the very sites of worship and teaching. All else belongs to the private or public realms. This separation of worship from civic life has, from the outset, divided Muslim art into two clearly distinct categories: religious and secular. Aniconism is the feature that would, for centuries, characterise the former. Whereas in the latter, the figurative representation of humans and animal is plain for all to see. Figures of people or animals are used in decoration on plaster, ceramic, wood and glass. They can also be seen on everyday utensils, objects made of pottery, marble, ivory or other material. This also goes for the pages of literary or scientific books in general.

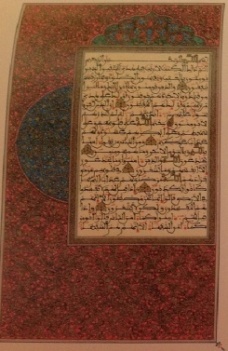

For Muslims, the Quran contains the word of God and is therefore sacred. The eminent position taken up by the book in Muslim culture along with the aesthetics specific to Arabic script played a considerable part in the development of ornamental calligraphic styles. This did not leave much room, by comparison, for the painting or representation of living beings. Over the centuries, this issue gave rise to numerous debates and controversies among scholars whose interpretations diverged. The affirmation of “the oneness of God Sole Creator” leads many of them to conclude that the figurative reproduction of living things is a blasphemous appropriation of a divine attribute. From the concept of this divine quality, the interpretation of some Quranic texts, as well as the contents of some Hadiths sprung censorship, nay an actual phobia of such productions as statuettes or images of an anthropomorphic or zoomorphic nature. This iconoclastic position had its rationale in the awareness of a risk that such productions may be adored.

Informations[1]

Informations[1]The traditional chronology of Islamic civilisation, namely the appearance of the religion in the Arabic peninsula, its advances as well as the splendours and decadence of Muslim powers over societies living over vast territories underscores the main stages of Muslim art. A figurative art pre-existed and held up under various guises after the advent of the Muslim faith. The Arabs adopted civilisational elements of the countries they conquered and where image had a strong presence. The production of Abbasid Mesopotamia and Persia had a strong tie with the Sassanid tradition. Umayyad Syria soaked up Hellenistic and Byzantine imagery. Egypt maintained a strong tie with the Pharaonic and Coptic traditions, and Al-Andalus yielded yet another specific synthesis.