Figures and sculptures from the Umayyad period (661-750)

The first intimations of a specifically Muslim art go back to the Umayyad period, which is considered a period of transition from Byzantine to Abbasid art. Fabrics were a favoured outlet for figurative art, whether for the purpose of dressmaking or furnishings. Linen, silk and cotton cloths with motives of living beings were much to the taste of the caliphs. But that era's artistic production reached its peak in architecture. Masterpieces in that style include, among others, Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock – which Oleg Grabar rated Islamic art's first achievement – and Damascus' Great Mosque. Umayyad aesthetic influence would spread as far as Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, even after the fall of the dynasty. As for the earliest instances of images of living beings, they are to be found in pottery, glassware, ivory, metal or woven artefacts, where the repertoire of figurative representation is brimming with princely imagery, hunting scenes, everyday life and other themes associated to the zodiac, the months, seasons, etc.. Whether paintings or indeed sculpture, these works were to be found in royal establishments. The representation of men, women and animals accounted for an important part of the ornamental repertoire of these luxurious dwellings, to wit graphic accounts of the times extant in Qasrs[1]. The most significant are:

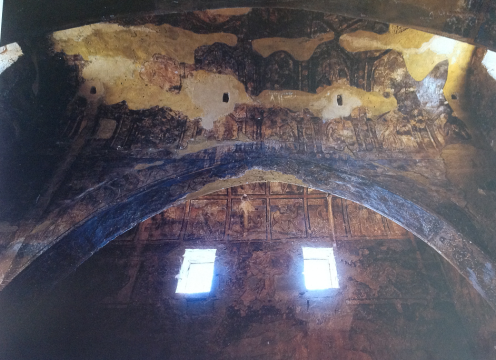

Qasr Amra: This architectural complex consists of a reception hall, a bath suite in the Roman style and bedrooms. The small Umayyad pleasure palace was discovered by Western travellers at the end of the 19th century. The building makes up for its modest size with abundant interior decoration including mosaics, some Arabic inscriptions in Kufic or Greek style as well as Polychrome frescoes, which develop a range of themes: people at work, hunt, animals, mythological characters, naked women, etc. Creswell provides a thorough and detailed account of the architecture and murals of the palace wherein he stresses the influence of a classical Roman heritage. Oleg Grabar makes more of the local character of the patterns, especially in the royal hunting and music scenes. Other specialists mention the Byzantine imprint while some find in the site a combination of Roman and Byzantine styles, be it in terms of fresco technique or in decorative subjects and architectural structure.

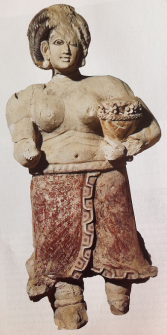

Qasr Hisham at Khirbat al-Mafjar (Palestine) and Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (Syria): the original sites were large, including a palace, a mosque, baths, a courtyard, towers, luxuriant gardens and a dam. The digs organised on both sites during the first half of the 20th century have brought to light the existence of sculptures adorning walls and cupolas as well as of stucco statuettes representing animal and human figures. According to Volkmar Enderlein, the techniques used in the stucco work as well as the themes extant in Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi are drawn from Sassanid aesthetics. The floor frescoes combine eastern and western traditions. Conversely, there is hardly any figurative representation in the mosaics that also decorated the floors but have left few traces.

Informations[2]

Informations[2]

Informations[3]

Informations[3]

Informations[4]

Informations[4]