The propagation of miniature during the first two Abbasid centuries

In many ulterior accounts, the early phase of the Abbasid caliphate is referred to as a golden age. The caliphs showed a good deal of interest in the arts of the regions under their domination where painted imagery was widespread. The 12th century saw the development of an illustrative painting style with a strong Sassanid flavour: miniature painting. Its practitioners hailed from Persia whence caliphs wishing to enhance this ancient practice sought them out. It found an outlet in the production of numerous manuscripts – translations into Arabic of tales from India, Greek treatises, a range of scientific, technical and literary works. Illumination, an invaluable source of information and the mirror of an era, fulfilled both aesthetic and didactic functions. Besides its decorative value, it proved a precious illustrative tool towards enhancing the text. It helped understanding the material thus increasing the pleasure of reading and boosting the influence of the moral teachings carried by literary works.

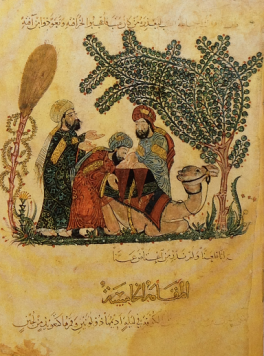

Miniature painting was universally adopted and soon made the names of painters like Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti[1] who complemented with illustrations one of Arab literature's masterpieces: Al-Hariri's Maqamat. Al-Watisi's illuminations evince a distinctive Syro-Byzantine style – so much so that some images reproduce Biblical characters found in Christian manuscripts. The composition's basic background remains fairly clear and simple with oversized figures. Among other manuscripts from that period Ibn al-Muqaffa[2]'s translation from a Persian re-work of a Sanskrit book of tales, Kalila Wa Dimna stands out. The text is supported by illustrations showing animals – the leading characters – and landscapes in settings combining naturalist and naïve traits.

Informations[3]

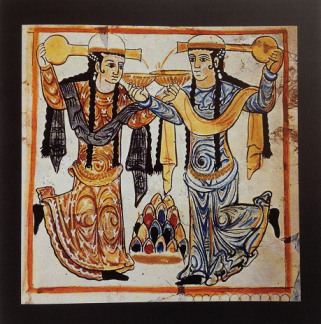

Informations[3]Besides the technique, which varies with regions and styles, illumination proposes a vast array of subjects. The most frequent themes are the life of the Prophet of Islam, folk epics, scenes of palace life, tales etc. Fresco fragments and other items discovered in Samarra, once the Abassid capital, show that – much as happened in Umayyad days – the Abbasids also tolerated the presence of figurative imagery in the wall paintings and on other utensils within their palaces. These paintings treat classical Hellenistic and Byzantine themes, namely wild beasts, naked women and hunting scenes.

Informations[4]

Informations[4]