The Catholic response

From the mid sixteenth century the supporters of Catholicism also showed they were aware of what was at stake in the literature of martyrology. They rejected the protestant creation of martyrs and were keen to find ways to frustrate it by eliminating elements of it in is judicial processes; this is how heretics who were tortured and burned would be labelled by the judicial process which condemned them, so in 1566 Marguerite de Parma[1] , governor of the Spanish Netherlands, ordered the Valenciennes rebels to be hanged as criminals under common law rather than sending them to the stake, a punishment reserved for heretics. In general, their narrative of the ‘troubles' depicted the Protestants as lawless, faithless ‘rebels' for whom religious freedom was merely a pretext.

But the Catholics also produced their own martyrologies in response to those of Crespin, Van Haemstede and Foxe. The first and best known of these was that of Richard Verstegan, an English Catholic refugee in Antwerp who had put his talent as an informer to the service of Philip II of Spain[2]. Published secretly in Paris in 1583, its exact title was Brief description des diverses cruautez que les Catholiques endurent en Angleterre pour la foy, often abridged to Théatre de cruautez des hérétiques de notre temps (Theatre of heretic cruelty in our time). Supported by engravings, he shows the treatment of Elizabeth I's Catholic subjects. In later editions he also gives accounts of bloody episodes in the Revolt of the Netherlands and the French wars of religion, emphasising throughout the oppression of the Catholics by the Protestants. Clearly he omits to mention the violence perpetrated by the Catholics, just as the Protestant martyrologies are silent on Catholic martyrdom. For the section on France, Verstegan relied on La République Chrétienne en forme de commentaire (Commentary on the Christian Republic) by the polemicist and Catholic theologian Matthieu de Launoy[3] , published in Paris in 1579. The work was very influential.

Text and image are intended to play on the conscience and strengthen sectarian hatred. One of the engravings from Verstegan's martyrology was displayed in the Saint-Séverin cemetery in Paris on the day before Saint John's day in 1587 in order to excite the anger of the Catholics. The main strength of the Théatre des cruautez des hérétiques de notre temps is certainly in its very violent and graphic illustrations. This distinguishes it clearly from the Protestant martyrologies, which are more austere and less accessible Some of Verstegan's iconic motifs were reproduced in church frescoes and in collections of images, which ensured that they were widely disseminated in the whole of Catholic Europe at the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth century. At the same time, Protestant martyrologies declined, suffering from the Protestant distrust of images.

According to Frank Lestringant, Verstegan's work is “an atlas of sacred geography which maps those places sanctified by the blood of the new martyrs throughout the whole of Western Europe.” It is a theatrical panorama connected to the geographical ‘theatres' such as that of Abraham Ortelius[4]' Theatrum orbis terrarium . The idea is to make the reader see the martyr's experience as a vicarious witness. The techniques of illusion such as angular perspective, with several vanishing points, bring the viewer into the scene.

Informations[5]

Informations[5]Foxe's Book of Martyrs undoubtedly served to consolidate English identity in the cause of the Anglican Protestant cause. Verstegan's Théatre des cruautez des hérétiques de notre temps, for its part, contributed to the reinforcement of traditional Catholic solidarity. Anne Dillon has shown that the construction of English Catholic identity as victims and sometimes rebels owes much to the work of Verstegan and other martyrologies of the genre.

In reality, martyrologies are often linked to a particular region defined by their language and confessional provenance. At the same time, many of them were widely disseminated beyond national frontiers. While benefiting from the international networks of their denomination, they helped to cement them. The historian studying them should not underestimate the central role that martyrs played in the enterprise of religious propaganda. Martyrologies have always been instruments of celebration of their own creed and hatred of others. They systematically insist on the innocence of the victims and the cruelty of their adversaries. Their dissemination is an extreme method of ensuring that the message is received.

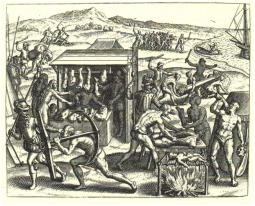

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the Protestants expanded their ideological struggle to the Americas, in adopting the denunciation of Spanish atrocities by Bartolomeo de las Casas[6] . An engraving by Théodore de Bry[7] illustrating the Frankfurt edition of 1598 of the Très brève histoire de la destruction des Indes clearly suggested a parallel between the Indian condition and Christ's road to the cross. Cannibalism amongst the Indians was tolerated by the Spanish; the conquistadores therefore encouraged Indian barbarity [8]. The image also suggests a link between Catholic communion and its ‘Dough God[9]' and cannibalism. “In the Indian, trampled on and oppressed, tortured and burned alive, the Huguenot found a brother in suffering in a sort of double allegory”, observed Frank Lastringant. These victims were not properly speaking martyrs as they were not subjects of evangelism; all the same they were closer to Christ than the Catholics, whose barbarism they helped to reveal, according to their enemies of the period.

Informations[10]

Informations[10]