Jewish women and the intricacies of Jewish emancipation in Europe (1790/91-1917) – Vincent Vilmain

Women in the Jewish tradition

The treatment of women in the Mosaic tradition takes pride of place in the toolkit of Christian-inspired anti-Judaism. The notion of women's debasement in the Jewish tradition only surfaced at the beginning of the 16th century with the 1519 publication of the Juden Büchlein (lit. Jewish manual) by Victor von carben[1] . The trope then took hold, to reappear in Johann Eisenmenger[2] 's 1700 Entedecktes Judenthum and proliferate in the 19th century, especially among American and German Protestant theologians and, to a lesser extent, among Catholic theologians too. The salient facts brought up to testify to women's debasement are their exclusion from the minyan, and from initiation into Torah[3] study. This could readily be used to extol Jesus's attitude towards women, and by extension that of the Church.

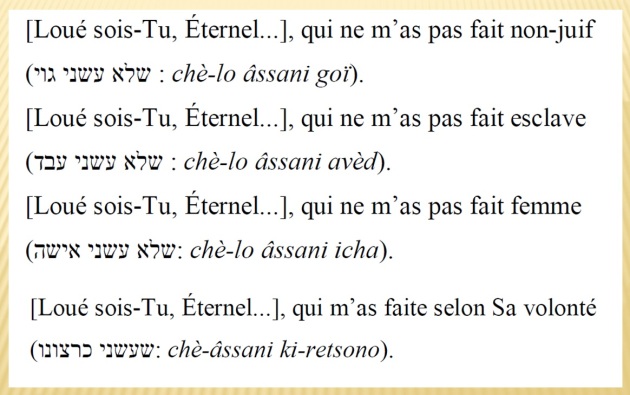

Quintessentially, three of the morning blessings that each and every worshiper was expected to pray every morning were framed in the negative . The third among them reads: “Blessed are You Adonai our God, Ruler of the Universe, for not making me a woman.” The women called upon to say this prayer have, since the 16th century, fell back on the following formula: “Blessed are you... for making me according to His [sic] will.”

Blessed are you Adonai... for not making me a gentile Blessed... for not making me a slave Blessed... for not making me a woman/ or making me according to His will Blessed... for making me according to His will |

The origin of this blessing is to be found in the Babylonian Talmud (Menahot, 43b). The most classical justification for this formula – and which is still argued in orthodox Judaism in favour of upholding this blessing – can also be found in the texts of that period: women, as they do not have to observe all the commandments (mitzvoth), are put at a disadvantage and men must rejoice that they are so closely governed by God (JT, Tossefta). In fact, many texts by the most erudite specialists of Judaism show that the understanding of this blessing is quite different. Rashi[4] justifies it thus: “for a woman is a slave to her husband as the slave is to his master” (BT Menahot 43B). Many, on the strength of an ontic gradation, do not stop there, viz. Nachmanides[5] (8th century) as well as the author(s) of the Zohar[6]. Thus inferior or deficient, women must be subordinated to men. Modern orthodoxy still upholds the difference in nature between men and women but commend their complementary. Men are from Chokmah, or wisdom, and women from Binah, or understanding.

All other exclusions spring from this principle. The Jewish woman is denied the study of the Torah because it was entrusted to the sons of Israel according to the account in Exodus and because teaching her the Torah would be tantamount to teaching her tilfut (frivolity if not wantonness) according to the Talmud (BT Sotah 3). The Oral Law is likewise forbidden to her. She is exempted from most regular mitzvoth so that they do not get in the way of her duties to the household and to the family. In exchange, the Talmud promises her greater happiness in the life to come for enabling her menfolk to study the Torah (BT, Berakhot 17a). Furthermore women are disqualified to testify, to pray in public, to read the Torah, or to sing as their voice is a call to unchastity (BT Berakhot 48a).

However, a fresh reading of the whole of the Jewish corpus (Tanakh[7] , Talmud, Midrashim[8] ) with the support of archaeological sources show that the cause of this blatant misogyny is essentially to be traced to the rabbinic selection and interpretation of the texts. Thus Genesis does not introduce any subordination between the sexes: “So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them” (Genesis 1:27). A number of books of the Bible show women in the highest positions: judge, queen, prophetess... Myriam and the women of Israel sing (Exodus 15), Hannah prays (1 Samuel). The Alliance is accomplished in the presence of women, as is the handing down of the Ten Commandments. In the Talmud, Ben Azzai advocates – against Eliezer – the teaching of the Torah to women (BT Sotah 3) etc.... Besides, archaeological studies of synagogues anterior to the fall of the Second Temple and the rise of rabbinic Judaism show that women exercised higher functions (archisynagogos) in the synagogue though it is not clear which.

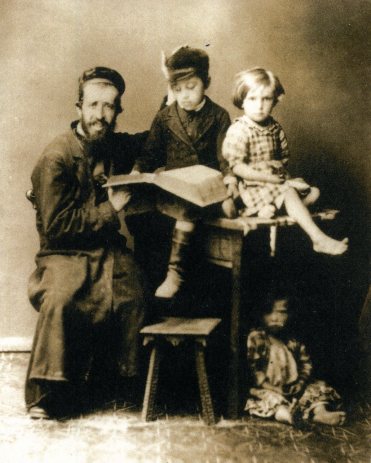

Still, the founders of rabbinic Judaism and their successors' precepts presided over the fate of Jewish women up to the emancipation era – and beyond as witnessed by An-Sky[9] 's photographic documentation of his ethnographic study of Russian Jews at the turn of the 20th century. Are we to infer that the diasporic and communal context rather favoured the situation? The fact is that in the 18th century, Judaism still marginalised Jewish women. Their knowledge of the religion was very superficial: in the Ashkenazi world, it was restricted, at best, to the perusal of the Tseno Ureno[10] , a commentary of the Torah published at the beginning of the 17th century or to its Sephardic counterpart the Me'am Lo'ez[11] . Several prayer books for women drafted in Yiddish have nonetheless survived to this day that testify to an intense liturgical life. It remains that they had likely been drafted by men and their content reinforces the tradition's stereotypes of Jewish women.