Lebanon's Maronite painters between figurative and abstract art

The State of Lebanon was proclaimed on 1 September 1920 as the Ottoman Empire was dismembered by the French and British colonial powers. During the preceding half-century, the Maronite and Druze communities had eventually come to a modus vivendi achieved through the framework of Mount Lebanon's Mutasarrifate[1] . Meanwhile, coastal cities such as Tripoli, Jbeil, Beirut, Sidon, where the presence of Sunni and Greek-Orthodox populations was more important alongside other religious groupings, had been under the direct authority of the Ottoman power. This period saw the cultural renewal that flourished in the literary and artistic fields in particular and became known as the Nahda[2]. It thrived on the development of a network of schools and colleges, the creation of reviews and newspapers as well as contacts with European merchants, scientists, travellers and other missionaries of the Protestant and Catholic persuasions. Now, religious communities underpin the demographic configuration of this evolving national society. Religious references – mostly Christian or Muslim – pervade the diverse aspects of social life and partake in what made Mount Lebanon then Lebanon a sacred land, a land of holiness, custodian of an ancestral past.

In line with the scrutiny of 12th to 15th frescoes and icons still extent in the churches, Christian thinking on imagery closely links representation with religious concepts steeped in the Bible, the Sacred Texts and their commentaries.

Representation is never envisaged without this framework. Frescoists, iconographers, miniaturists celebrated the beauty of the world in Christ according to the tenets of their faith and were nothing less than the inspired keepers of the divine treasure. In the case of the Maronites, who have had a college in Rome since the 16th century, this inheritance doubles up with that of a thriving Italian tradition. The influence flows, which also apply to other uniat[3] Christian communities, are complex. In the 19th century, they swelled in the wake of migrations – temporary or otherwise – towards Egypt, Europe or the United States. Beirut became a hotspot for cultural contacts and an internationally recognised school evolved, albeit remote from major centres.

Daoud Corm[4] is considered the doyen of this school of Lebanese painters. Famous for the paintings he created in churches and convents, he pioneered a major phase in Lebanese contemporary art, freeing it from amateurism to bring it in the mainstream of international painting and its masters. His talent rested with integrating into a personal perspective the style of major Renaissance painters he had discovered when studying in Rome. Raphael[5], Michelangelo[6], Veronese[7] and Titian[8] underpin his artistic culture. His critical theory and his art are tied in with his religious thinking.

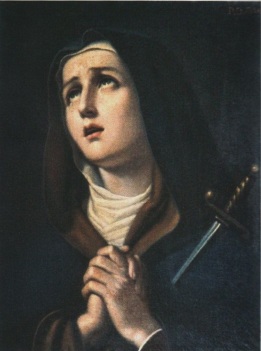

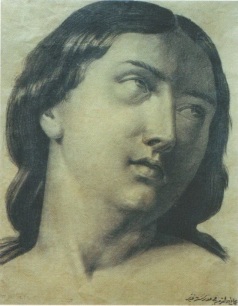

Daoud Corm' primary expression of compassion passes through the image of the Virgin Mary thus her representation must come as close as possible to perfection. His canvas Portrait of Mary as a Young Woman is dominated by the colour blue, symbol of feminine innocence. The facial features seek to communicate God-given gentleness. In another piece the feeling of sadness is underscored by dark colours and tears welling in the eyes. Comparison with his early works, such as the 1869 Virgin with Child, show a remarkable evolution. His treatment of hands is significant. For Corm, the disposition of the fingers, the fluidity of the drawing, the variations in shading partake in the expression of the idea of perfection he seeks to achieve. As for the upward glance, it purports to convey spiritual holiness. In his representation of Jesus Christ, Daoud Corm displays his profound knowledge of Christian iconography from the Byzantine era to the present. In the icon of Jesus' Sacred heart, he resorts to a classical geometric grid, a subdivision of the canvas into four horizontal plans and a triangle that enable him to show Jesus at the centre, the focus of light and love, though still carrying his cross of suffering. The setting of Jesus, the boulders, as well as the circular motion of angels (symbol of suffering below, illuminating Christ above) and of saints suggest that the piece draws on Raphael's Transfiguration. Both artists' intention to teach Scripture by means of imagery is plain to see.

Informations[9]

Informations[9]Within the School of Beirut, a new generation shows an interest in non-figurative trends; one of its best known exponents is Saliba Douaihy[10]: “He draws a new aesthetic conception from his Mediterranean inheritance and slowly progresses towards non-figurative painting where the subject's visibility is to become secondary and bow to the mastery of colours in a stark stripping of forms which comes to yield a highly individual style”. (Brahim Alaoui). Saliba Douaihy paints on large canvases in a slow rhythm allowing much room for abstraction – in sharp contrast with earlier generations. However, in his religious works in particular, he resorts to visual stereotypes that allow the identification of the subjects. Attributes attached to God or to the Virgin, allegorical personifications and postures mentioned in Scripture offer clues as to the figures represented.

In Saliba Douaihy's pictorial representations – say, for instance in the frescoes of the church at Diman – the divine light is materialized in vertical and horizontal lines: length and verticality aim to express both Jesus transcendence and his centrality, width and horizontality evoke the human dimension. Here, space and time are disconnected from everyday life, they echo a spiritual world and are given an abstract tempo. Stained glass offers Douaihy another support for his religious art: its very filtering of light offers an image of divine transcendence. It is as open as canvas to the use of stylized forms but affords the possibility to play on the intensity of colours to introduce, there again, references to Scripture. Through his stained glass work and the depth of light it allows, the artist seeks to reach a delicacy of feeling he fears lost.