The Mandala of the two Worlds

The Womb World Mandala represents the innate potential for Buddhahood in every being, symbolised by the character ri[1], meaning “principle, reason, ideal”. The Diamond World Mandala represents the progress of sentient beings towards Enlightenment thanks to “wisdom”, symbolised by the character chi[2]. These two aspects ri and chi, innate reason and wisdom, are indissolubly linked and neither can exist without the other, as framed in the formula “principle and wisdom are non-dual” (richi funi). The association between the two mandalas is thus perceived as two sides of the same coin. While no Chinese pair of mandalas has survived, the most ancient Japanese Mandala of the two Worlds, dating back to the 9th century, is that of Takao (830), named after the temple in Western Kyōto where it is kept. Though there are undeniable iconographic differences between mandalas, they are nearly always minor: beyond stylistic variations the major figures match up, only secondary figures change.

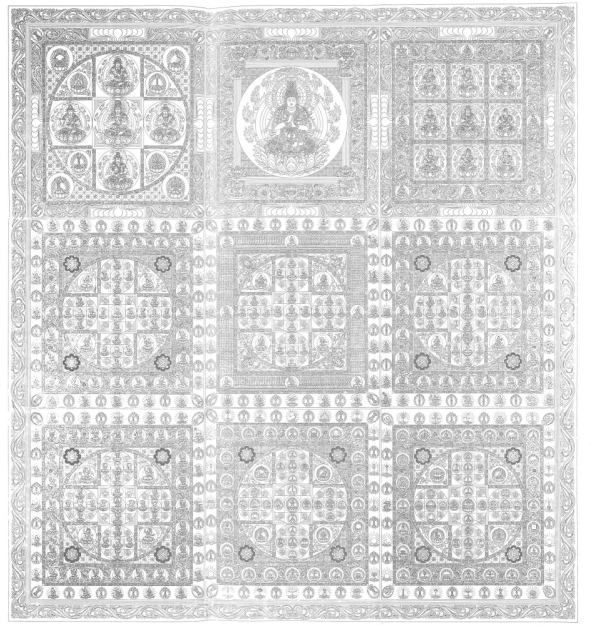

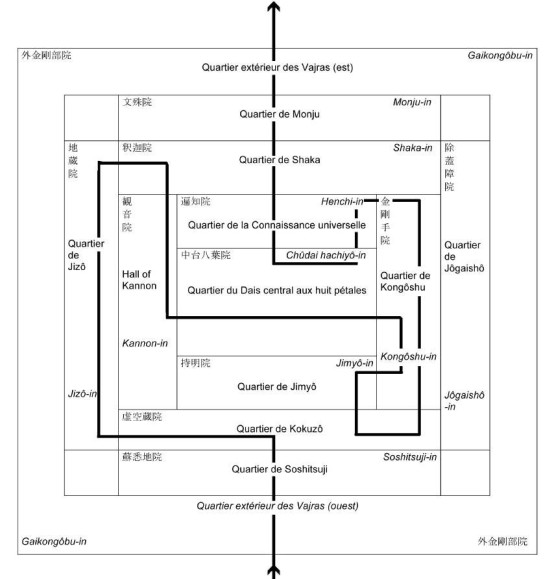

The Womb World Mandala represents the cosmos of Buddhist Enlightenment seen from the standpoint of compassion, which is symbolised by the womb (the uterus) understood as a passive element, the “substrate” common to all beings. The deities represent the diverse forms compassion can take; they are the means to achieving enlightenment. The lotus is the primary symbol of the mandala: the grain already carries the germ of its blossoming and thus corresponds to the innate potential for Buddhahood while the compassion that enables the maturation of the grain is the “womb” whence it shoots. The images of the womb and the lotus both implicitly carry the idea of gestation, growth and birth (or realisation). This mandala adopts a concentric structure around one section, the “central quarter of the eight-petalled lotus, Hall of the Central Dais Eight Petals”, where the universal Buddha (Dainichi[3]) resides, surrounded by eight deities (four buddhas and four bodhisattvas) symbolising his virtues. It is divided in twelve halls distributed over three or four sections, depending on whether the central hall is included in the count or not. The deities are seated on red lotus petals. The colour stands here for compassion but also for the human heart, within which Buddhahood is to be attained. The diverse halls, sections and deities are interconnected by a complex symbolic system and pertain to a not wholly symmetrical structure. A mandala's fundamental dynamics is driven by mutual exchange: the deities at the centre emanate outwards (the closer one gets to the periphery, the closer one gets to the human world) and conversely, all beings partake in a move towards the centre, that is towards the perfection of Buddhist enlightenment.

Informations[4]

Informations[4]

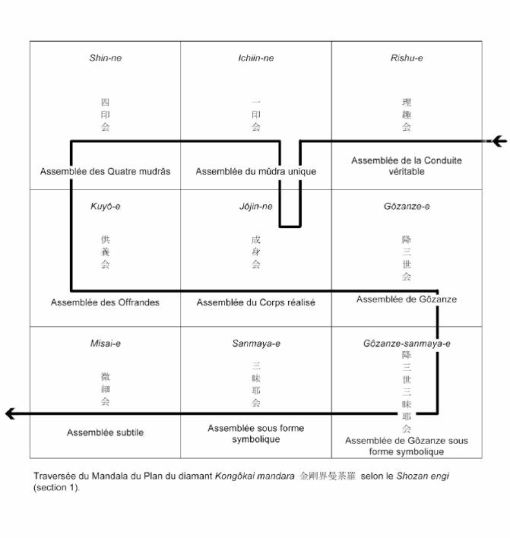

The Diamond World Mandala represents wisdom. Diamond is associated with indestructibility. The Indian term vajra (kongō in Japanese) can also refer to a thunderbolt, the weapon associated with Indra, the King of Hindu gods, the slayer who destroys ignorance. Here, the notion of “world” or “realm” singles fundamental nature as a distinct body; it represents the distinction between objects of knowledge or cognition, whereas the womb corresponds to innate or original nature. Its structure is comprised of nine assemblies, taking the shape of squares of equal size, which were originally independent mandalas. The Dainichi is seated at the centre of each of the nine assemblies, the central one being the most important. Five sections are represented, again leading from transcendental to phenomenal from the central assembly outwards.

Informations[5]

Informations[5]

Informations[6]

Informations[6]

Informations[7]

Informations[7]

La fonction rituelle des mandalas ne se laisse pas définir de manière littérale ou directe. L'acception commune veut qu'ils soient des supports de visualisation ou de méditation. La réalité est à la fois plus simple et plus complexe. De même que toute autre image bouddhique, les mandalas sont des icônes au sens défini par l'historien du bouddhisme Robert Sharf d'une « sorte spécifique d'images religieuses dont on croit qu'elles prennent part ou participent de la substance de ce qu'elles représentent ». Sharf ajoute à cela qu'une « icône ne ressemble pas seulement au divin, elle participe de sa nature même ». Une icône bouddhique est donc davantage qu'une simple représentation. Elle n'est pas seulement habitée par le divin, elle est littéralement vivante, dès le moment où elle est consacrée, par une cérémonie qui se dénomme d'ailleurs « ouverture des yeux »[8] . Une telle aperception explique également que nombre d'images ou de statues sont perçues comme ayant des vertus apotropaïques, thérapeutiques ou salvifiques. Pour le bouddhisme, les images et statues ont ainsi un potentiel qui dépasse très largement celui d'une simple représentation symbolique, ou d'un simple support rituel.

D'un côté, les icônes bouddhiques sont donc « vivantes ». De l'autre, Kûkai explique que les images bouddhiques et les mandalas sont l'expression par excellence de l'univers bouddhique, soit de la réalité ultime, et qu'ils la représentent d'autant mieux qu'ils ne passent pas par le langage ordinaire. Les mandalas sont l'un des outils grâce auxquels les pratiquants peuvent court-circuiter le samsâra[9] ou cycle des renaissances et parvenir à l'Eveil. En effet, le bouddhisme ésotérique a pour spécificité par rapport à la plupart des autres courants du bouddhisme d'affirmer la possibilité d'atteindre à la réalisation bouddhique dans cette vie même, littéralement « dans ce corps même ». Puisque le potentiel de bouddhéité est inné, qu'il est latent en chaque être vivant (y compris dans les plantes), il suffit de parvenir à l'activer pour quitter le samsâra. Pour arriver à ce but, le bouddhisme ésotérique se sert d'un appareil rituel sophistiqué dont les mandalas, en particulier ceux de la Matrice et du Plan du Diamant, font partie intégrante.

Pour atteindre à la bouddhéité, il faut parvenir à ressentir l'identité foncière entre le soi individué et l'univers tout entier, soit la non-dualité exprimée par la « non-séparation entre Raison innée et Connaissance » (richi funi) que symbolisent les deux mandalas. L'immense complexité des rites du bouddhisme ésotérique a pour but d'amener cette prise de conscience et de la rendre permanente. De même, comme le souligne Robert Sharf, les mandalas, ainsi que les autres icônes bouddhiques, doivent être compris non pas comme une simple illustration symbolique ou un support à la visualisation, mais comme un lieu de manifestation du divin ou de l'universel. En présence d'un mandala, le pratiquant est appelé à ressentir l'union foncière de tous les éléments de l'univers entre eux, à commencer par sa propre identité avec l'essence divine représentée.