Major gods of the North African pantheon

The peoples of Libya were exposed to numerous religious influences: Egyptian, Phoenician/Punic, Greek and Roman. This is documented essentially by epigraphic texts discovered in large quantity in the ruins of temples and sanctuaries as well as on other archaeological sites. This documentation shows that the Libyans highly valued fecundity and procreation and sought in natural powers their protection from malefic genies[1]. It does not always account for the origin of the gods, though. As a result of cultural and commercial contacts, Libyan gods shifted towards the gods of the Mediterranean region: they often boasted the same powers and the same attributes.

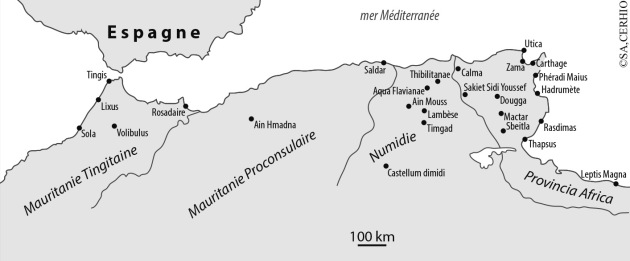

Thus, studies delving into ancient Africa refer to some ten deities such as Gurzil[2], carved from wood, among the Mazices[3], or perhaps Bona Dea, a goddess of womanhood. There are also gods hailing from Africa such as Mercury, son of Jupiter and Maia, daughter of Atlas whose children were heroes in the Greco-Roman tradition. Each region and each town had a god or a goddess of fecundity, mother and carer, giver of and tender to life whether animal or vegetal; the most important was Tanit[4], become Caelestis in the Roman era, to which must be added he Libyan Hercules[5]. Furthermore, if Herodotus[6] is to be believed, the Libyans were the first to worship the god Poseidon[7], as indeed Antaeus and Athena[8], goddess of wisdom. In highest antiquity, Neptune-Poseidon was seen by the Libyans essentially as a god of fresh waters having also the power to cure several illnesses.

Informations[9]

Informations[9]During the second millennium before our era, many gods from Egypt – not least the goddess Isis epitomising woman as wife and mother, as vital force – were venerated in varied parts of the Mediterranean basin. The oracle of Ammon, the highest god to the Libyans was faithfully attended by the Eleans[10]. This horned god was famed for his truth telling. He was represented by a ram whose head was crowned by a solar disc, an image frequently found in the Atlas region. The Libyans only knew the theonyms Ammon without the ‘H' but this god was honoured by the Phoenicians under the name of “Baal[11] Hamon”, who, some historians suggest, is none other than the Egyptian Ammon honoured throughout North Africa. His name means « possessor and master of heat »

or « god of the sun »

. Some contemporary authors think that his name is drawn from the radical HMM which means « radiant being »

, Baal Hamon being then understood as « lord of the braziers »

. Also noted is his name of Baal Qarnaim « Lord of Two Horns »

, whose title was corrupted in Roman times into Saturnus Balcaranensis. Baal Hamon was the great god protecting Africa, who became assimilated in the Roman era to the god Saturn; but he gave precedence to Tanit Pene Baal meaning Tanit Face of Baal (or of the « Great Lord »

) as attested by votive inscription where he nearly always appears in second position.

Among famous Libyan goddesses, Tanit took pride of place. Her name is to be found inscribed on stelae in Phoenician-Punic inscriptions, as Tnt, or Tynt, along with an equilateral triangle topped by a horizontal line and a circle, the anthropomorphic figure known as the “Tanit symbol”. The etymology of her name remains mysterious although it may be connected to the word Nit meaning “alone”. A Latin inscription discovered at Aumale[12] refers to a ceremony in the honour of Tonait. The origin of this goddess still raises many questions for the specialists whose conclusions diverge. Some reject the goddess's Phoenician origins on account of the absence of her name from the texts found at Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) and in Tyre. Others, on the contrary, assert her Phoenician origin speculating that her name in Phoenicia was different, becoming “Tanit” in Carthage. Others still have not dismissed the idea that Tanit was a Libyan deity for she had been venerated by the Berbers, notably in some tribal settlements which have set special and symbolic store by women within Libyan society and adopted her as a symbol of the force impelling fertility and procreation.

Within this mythological framework ancient peoples included demigods alongside the gods. Among the former figure such pastoral divinities as the nymphs[13] as well as other minor divinities. In Roman days, Jupiter reigned supreme. Rome's every feat resulted from the munificence of this God dwelling in the aether, the highest region in the heavens. He overcame all obstacles, no one could defeat him. He helped the weak and was the world's mainstay. He was at the source of all things and all beings. He had the power to advance, to stall, to sustain or to overturn events, to put an end to drought. Several feasts were organised to honour him. On the 15th of March, May, July and October and on the 13th of the other months a white ewe was sacrificed to him. The North-West of Libya was Atlas' domain, and the place of his encounter with Perseus: « Friend, if high birth impresses you, Jupiter is responsible for my birth. Or if you admire great deeds, you will admire mine. I ask for hospitality and rest. »

Atlas remembered an ancient prophecy. Themis on Parnassus had given that prophecy. « Atlas, the time will come when your tree will be stripped of its gold, and he who steals it will be called the son of Jupiter. »

The giant's daughters were married to gods – or, known as the Hesperides, were the keepers of the golden apples. Some authors assimilate Atlas to another giant, the famed Antaeus. To forestall drought, the Libyans resorted to magic or appealed to the gods. It is reported that a Roman province governor was persuaded by a Moor[14] to call upon magicians and their incantations to bring rain, reportedly with miraculous results.