Regnum et sacerdotum : the king against the church

Canossa

The conflict that had been smouldering since the middle of the 11th century flared up in 1075 with the question of the investiture of German and Italian bishops. Being both the King's vassals and the church's agents, the German bishops were bid declare their loyalty as the conflict escalated. Torn between keeping faith with the Emperor and with the pope, the bishops gradually abandoned the imperial side, thereby weakening the authority of the Germanic monarchs. The conflict also offered the nobles the opportunity to gain the upper hand. In 1076, released by the papacy from their oath of allegiance to the excommunicated sovereign, the nobles chose to disavow Henri IV[1] and, gathered at Forchheim on 15 March, they appointed Rodolf of Rheinfelden, Duke of Swabia as head of the kingdom. The conflict drove the kingdom into a political anarchy over which neither Henry IV, his Canossa[2] submission notwithstanding, nor his son Henry V would ever really manage to impose their power. The Concordat of Worms, agreed in 1122 by exhausted parties allowed for a truce in this ongoing conflict. By distinguishing between a spiritual investiture emanating from pontifical power and a temporal investiture from the sovereign, the concordat provisionally pacified the relations between the pope and the emperor. However it gradually detached the bishops from royal power in the process and paradoxically brought them closer to the kingdom's lay princes as a body. The bishop's estates became alike the realm's other principalities from which nothing actually differentiated them in the eyes of the monarch.

The growing autonomy of the kingdom's princes, lay and ecclesiastical both, was at the same time reinforced by the universalist conception of imperial power. The imperial title, superimposed to that of king was obscuring the royal dimension of power. Busy asserting their position in Italy, the monarchs progressively deserted the royal framework leaving the exercise of power to the princes of the realm. Focussed on the justification and definition of imperial power, imperial jurists did not seek to define the nature of royal power in Germany. Testament to this confusion is the use of the same crown, the crown of Charlemagne, taken indifferently throughout the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries for both ceremonies, the royal coronation in Aachen and the imperial anointment in Rome. This ambivalence was echoed in official titulature: whilst the monarchs had no qualms in styling themselves rex or imperator, cumulating the crowns of Italy, Burgundy or, from Henry VI[3], Sicily, there is no word to identify the initial kingdom. From the second half of the 11th century, that of regnum teutonicorum would slowly achieve recognition which, framed by non-Germanophone jurists, de facto discarded its Slavic, Francophone and Italophone marches. It had little currency within the kingdom where the style of rex romanorum, king of the Romans, inaugurated by Henry II got slowly accepted. But this latter title is more resonant of the promise of and claim to the imperial title than of a Germanic anchoring. Thus the sovereign was, as from his coronation, defined as the emperor to be, the heir to the imperial throne, much more than as king of Germany. There was a de facto confusion between regnum and imperium.

Informations[4]

Informations[4]The failure of imperial claims

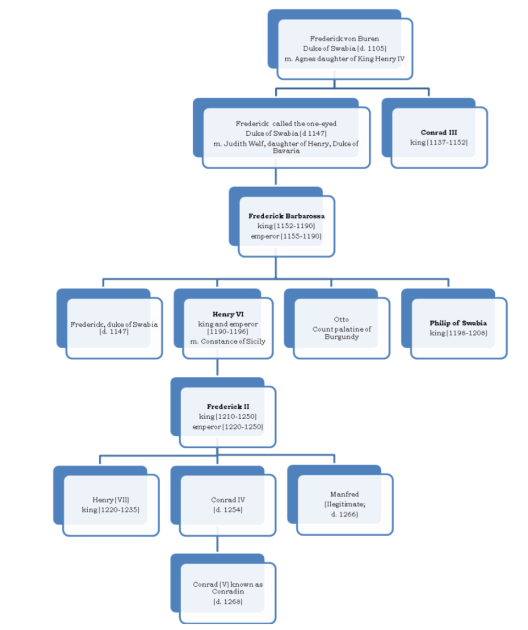

The bishops' growing empowerment, unacceptable to the supporters of the imperial party was by and large fought by the Hohenstaufen, not least Frederick Barbarossa. The Besancon episode rekindled a conflict that had never really been extinguished around the key point of the primacy[5] of the pope over the emperor. The accession of the Hohenstaufen to the throne of Sicily, as from 1189 heightened pontifical fears of encirclement by the Germanic monarchs and reignited a fight made unequal by the influence garnered by the papacy over the 12th century. The struggles between Henry VI and later especially Frederick II[6] and the papacy never let off throughout that monarch's reign; the emperor's death in 1250 marked the end of the imperial claims.

This autonomy of the nobles, incipient in the Concordat of Worms was broadly confirmed by the sovereign power in the years 1220-1230. By the Golden Bull of Eger 1213, the emperor renounced the right to attend episcopal elections and to his right to resolve disputed outcomes; he forewent his rights of regale[7] and of dépouille (spoils). By concession to the ecclesiastical princes (Confederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis) the king renounced in 1220 any right to intervene on church land, leaving them in charge of customs, coinage or fortification and conceding their de facto sovereignty. The privileges would be extended to the lay princes in 1231 (statutum in favorem principum), thus turning the Empire in a kind of federation of principalities where the royal tier no longer had any part to play. This withdrawal of central power is confirmed at Frederick II's death by a very real vacancy: the absence of an actual sovereign between 1250 and 1273 (Great Interregnum) provided evidence that the realm could dispense with royal power for its existence. The restoration of the empire in 1273 was conducted on fresh bases, respecting the quasi absolute independence of the principalities.

This retreat of royal power suffered by Frederick II is in stark contrast with the monarch's project for an ideal model of royal government in Sicily, set in the tradition of Augustus' Principate, its princeps wielded his political power according to the Augustinian vision of the « City of God »

. The take-over of the kingdom of Sicily was supplemented with a remarkable law-making effort as witnessed by the Constitutions of Malfi which, promulgated in 1231, set down the centralisation of royal power. What with his struggle with the papacy, Frederick II would only three times show north of the Alps throughout his reign (1212-1220, 1235-1236 and 1237). However he arranged to be represented by his son, Henry, whom he had elected king as early as 1220. The eventual Staufer defeat marks, even more than papal victory, the vanishing of kingship in Germany : rather than the church, the princes as a body, whether lay or ecclesiastical, were all around beneficiaries of the confrontation. It would no longer be for the king but rather, collectively for the nobles to incarnate the realm and its continuity. The event consecrated the victory of the elective principle ; a few later attempts notwithstanding, kingship in Germany would be elective and royal power curtailed by that of the nobles.