Kingship and its modus operandi

Introduction

The kingdom was born of the common will of the Princes of the old Carolingian kingdom of East Francia[1] to give themselves a king. Established in 888 with the election of Arnulf[2], of the prestigious descent of Charlemagne[3], it was from the outset conceived of as perpetuating Carolingian power. The 899, 911 and 919 elections would contribute to delineate the nature of Germanic kingship : an authority arising from the consensus between the major ruling families who had chosen to bring the entities under their control together under the domination of one single sovereign, guarantor of the legitimacy of a power they exercised only by delegation. The sovereign, born of one of the kingdom's ruling families drew his own legitimacy from the choice made by his peers, confirmed by the full rites of coronation and sometimes by force of arms. This sacred kingship was also a sacerdotal kingship and the close relations binding in its foundations royal power and the Church carried the germs of a potentially dangerous rivalry.

Sacred kingship Vs elective monarchy: Primus inter pares or Stirps regia?

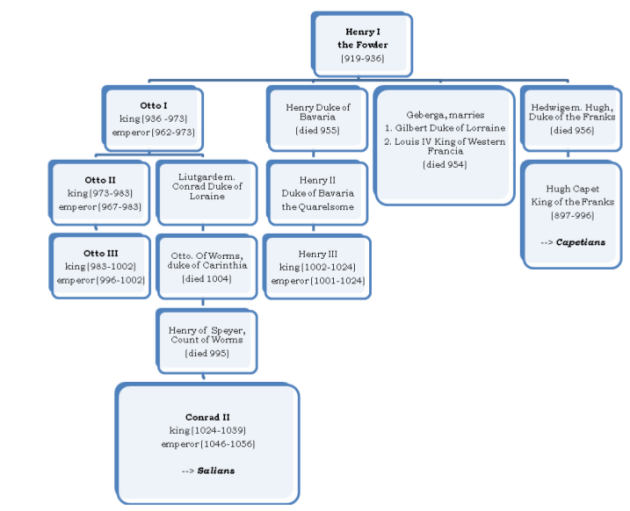

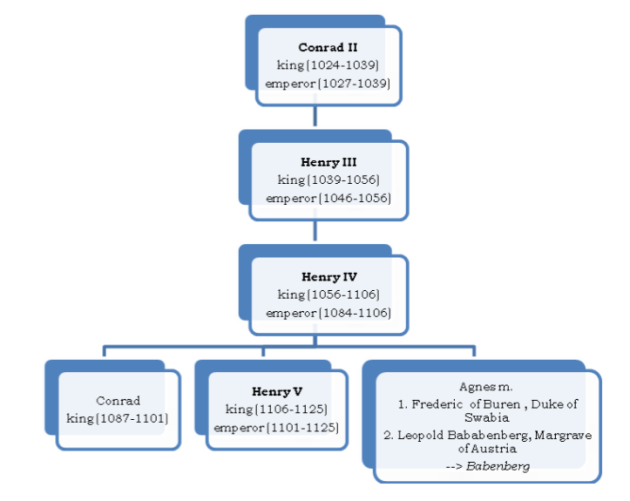

The elective principle underpinning Germanic kingship went against the dynastic conception[4] bound in the view of kingship inherited from the Carolingian era and so it was that the Ottonians succeeded each other quite regularly from 919 to 1024 as did the Salians from 1024 to 1125[5]. It only came into its own in situations when there was a power vacuum, as happened upon the death of Henry II[6] (1024) or Henry V[7] (1125) who died with no heir to succeed them. The nobles[8] mighty objections to this dynastic principle were manifest in the revolts that accompanied each succession: Only Henry III[9] in 1039 was spared a revolt as he accessed the throne.

Thus the nobles played a fundamental role in the king's rise to power: it is they, as representatives of the realm's peoples, who, by electing him, made the king. The ostensible respect of the elective process and of the rituals remained paramount for them as for the sovereign: the election was followed by the oath of fidelity, an acknowledgement of the regal nature of the power exercised by the new sovereign. It was only on the strength of that oath that the ceremonies of anointment or coronation of the king then his enthronement at Aachen in Charlemagne's palatine chapel took place; they formalised the nobles' choice and realized it in everybody's eyes.

The delegation of power

The realm originally had no institutions or unity. The basis for the sovereign's might arose first from his own landed property and wealth to which were added royal assets (fisc) and royal prerogatives (regalia). But the essence of the sovereigns' power rested with their capacity to impose their authority and exercise it. Thus the service of the king (servicium regis[12] )would only be carried out in so far as the monarch was in a position to exact it.

For want of a state administration, the management of such a vast conglomerate was impossible for the king who had to devolve part of his powers to established local aristocratic families. This capability to delegate authority or to regain it was both the hallmark of the sovereign's supreme power and the wellspring of the legitimacy of the nobles' power as well as a form of government. The nobles also took direct part in the exercise of power being part of the royal council or Hoftag (diet). The king would ask for their opinions and their decisions. The diet may well represent the realm's only actual institution; but its importance was due more to instituted practice than to any juridical foundation. The princes' power was outstanding and the kings all sought with variable success, to curb it and curtail their influence. The destitutions of incumbent title holders, the dismemberment of vast duchies handed down since the 10th century or the creation of new entities helped undermine the odd rebellious vassal or reward loyalty. But contrary to the drive observable in other Latin realms, not least the Capetians', the sovereigns did not seek to regroup vacant duchies. Though there existed royal property scattered about throughout the kingdom (Königslandschaften), there was no effort towards constructing a solid centralised royal estate. This model was also imposed on a royal power compelled to conciliate the nobles in order to remain at the head of a fragile conglomerate.

All told, we have as much a monarchy as an oligarchy. This collective dimension to power is confirmed by the traction of the elective principle. The nobles it is who collegially make the king, thereby indicating the assent of the realm's diverse provinces to the choice made by the titular sovereign when he appointed his successor himself. Hence their paradoxical attachment to the royal power: the main source of the nobles' power legitimacy rested with the greatness of a rich and powerful sovereign.