A crisis context conducive to Mahdism

The territory corresponding to today's Morocco was for centuries a crucible of the conflict between Iberian Christians and Andalusian Muslims. Ever since the 10th century, it had supplied an important quota of the armed troops needed when the Muslims launched an offensive against the Christians and it later bore the brunt of the retreat when the balance of power swung in favour of the Christians and forced the Muslims into defensive strategies as the Reconquista[1]progressed. Indeed, when, in 1415, the Portuguese succeeded in seizing the strategic port of Ceuta, the event marked the turn of the tide for Muslim supremacy in Andalusia and the beginning of modern European expansion. The fall of Ceuta left a lasting impression; it caused a mass response from the Muslims. More specifically it advanced a new dynasty's take-over: the Banu Wattas[2] called a jihad aimed at stemming Iberian invasions and recovering lost positions. They feature as reforming horsemen building up the internal unity of the « Moroccan nation »

[3]. They sought to develop a new type of power to fill the vacuum left by the flagging political regime of the Marinids after Abu Inan Faris[4]'s death. Many historians consider that monarch as the last defender of the « land of Islam »

against the Christians.

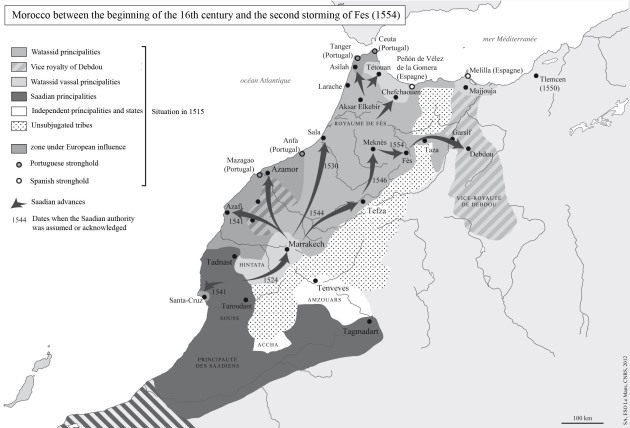

In spite of the momentum created by the jihad, the Wattasids were not able to recover all the lost territories, not even to coordinate well organised military campaigns against the Christians. The Portuguese managed to gain a foothold in many coastal points which served as supply ports for their ships and as strongholds whence to raid the country. The politico-religious authority of the dynasty was weakened as small independent entities emerged organised by tribal chiefs, Sufi teachers and town leaders. The Wattasids only really managed to control Fes, the Marinid capital, and its immediate surroundings. Their authority on more remote regions such as the Souss remained theoretical, nay symbolic. Their waning power encouraged a handful of regional chiefs to shake off their allegiance to the Makhzen and to assert their autonomy through raids against their neighbours or against Portuguese forts. The general trend was for fighting these battles without back-up from the central power: the period's accounts show that most Mujahidin relied more on their faith than on any strategy or military organisation, lead as they mostly were by disciples from the influent Jazouli brotherhood.

The economy was in turmoil after losing control of the Saharan trade which had placed the region at the crossroads between Black Africa and the North of the Mediterranean. One of the social consequences was an unbalance between the nomadic tribes who had hitherto controlled the Saharan commercial routes and the sedentary tribes. This background of generalised crisis strengthened the religious leaders' hand. The dominant discourse after the fall of Cueta remained centred on the need to bolster the faith by fighting the « Christian foe »

. The authors reporting this situation note that for many people at the time, the crisis is nothing if not the result of their rulers' weakness in defending the « land of Islam »

, whether in the Maghreb or in Andalusia. In the biography of saints this crisis is even presented as « divine retribution »

for evil deeds committed by the Muslims after their repeated defeats against the Christians. Such a climate is always propitious to Mahdism, the belief in the imminent advent of Islam's Messiah known as the « Al-Mahdi Al-Muntadhar »

, both a liberator and a reformer. This belief is present in the writings of many Sufis. Most famous among them in the 15th century was Mohammad Al-Jazouli[5] who, having declared himself the « reforming Mahdi »

set forth an educational, religious and political programme and took the fight to the Christians and their Muslim acolytes.