The role of religion in state building

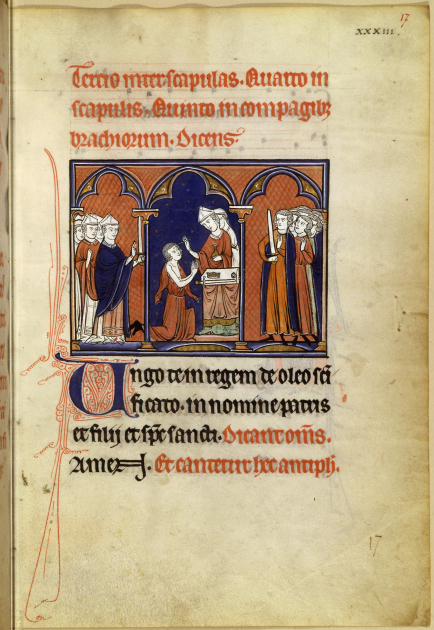

In Castile, Aristotelian philosophy, pressed into service to define royal power, reinforced its temporal nature. The accession of the king was not then marked by any particular religious rites as the coronation had been deliberately foregone in the middle of the 12th century. The new sovereign was content with the people's acclamation. In France, Philip the Fair has been seen, to a certain extent wrongly, as a harbinger of state secularisation whereas the coronation rites actually took him closer to the Christian representation of the priest-king. The anointment made the sovereign God's elect, and bestowed upon him powers thought to be miraculous. By refining the ritual in the 1300 ordo, he endorsed the use of this mystique. The representation of the soq royal, the royal mantle on his great seal is a reminder of his liturgical function. This idea underpinned a number of his actions undertaken in a spirit of religious reformation of the kingdom, notably the expulsion of the Jews[1] in 1306 or the onslaught against the Knights Templar started in 1307. Though several pamphlets sought a clear distinction between church competences and those of the État royal (the French Royal State), they only did so in order to counter Boniface VIII's theocratic ambitions (English version). The canonisation in 1297 of Louis IX[2], styled “Saint Louis” for the purpose is proof that France resorted to religious references to reinforce a royal power the legitimacy of which was more precarious than in Castile.

Informations[3]

Informations[3]In order to rest power exclusively with the king, Alfonso X's legal corpus implicitly rejected the authority of the Empire and that of the pope over his kingdom. Historiographic projects devised at the time prefer to lay claim to Castile's authority over other territories. To begin with, the Estoria de España (b. 1270) ascribed it a dominant role in the Iberian Peninsula, developing the notion of an Iberian Empire. The General Estoria[4] (from 1272-1275) extended to the world the king of Castile's universal pretensions with a view to compete with or to subsume the Holy Roman Empire. In France at the same period, the idea that the king of France and he alone is “princeps in his kingdom” as framed by Guillaume Durand in his (Speculum judiciale, (1271-1272) was gaining purchase. Under Philip the Fair the theory was radicalised with the term “emperor” replacing that of “princeps” during the conflict with Boniface VIII (Guillaume Durand the Younger's Memoir c. 1303 and the pamphlet Quaestio in utramque partem, 1302). The myth ascribing Trojan origins to the French monarchs was developed at the end of the 13th century in the Grandes Chroniques de France, written at the Abbey of St Denis by Guillaume de Nangis[5]. It brought with it the possibility to assert an anteriority to the church and thus to block the papacy's fiscal claims (note from the Royal Council c. 1296). Pierre du Bois[6] alone took this further adducing from a supposedly religious foundation the proclamation of Philip's universal power. Indeed, he fancied the king as a new Constantine[7], conquering Jerusalem (De recuperation Terrae Sanctae, 1305-1308 ), nay as a candidate to the Holy Roman crown (Pour le fait de la Terre Sainte, 1308) and asserted the moral pre-eminence of the kingdom of France on all others, including the Empire.

Also inside both kingdoms, royal sovereignty was emphatically affirmed. In Castile the king claimed a monopoly over law and justice. His relation to the legislative function, associated to wisdom by analogy with Old Testament models[8], , is effectively what earned Alfonso his nickname of “wise”. The exclusive role of the king in law-making, asserted in particular through a juridical treatise, the Espéculo (1255) marks a breach with earlier representations wherein the sovereign was only required to ensure that the law be enforced and, as the case may be, to reinstate it. This novel idea enabled Alfonso to justify his endeavours to overhaul the law and effect the legal unity of his realms. French theories in the days of Philip the Fair were less innovative and were essentially aimed at subordinating ecclesiastic jurisdiction to the royal courts, which was the cause of the second conflict with Boniface VIII. The object here was, in Louis IX's footsteps to make much of the exercise of justice by the king. Thus appeared in the regalia[9] the main de justice, a variation on the ancient rod. Philip clearly set himself up as pursuing his forebears' action by having their statues erected in the great hall of the royal palace where justice was rendered.

Informations[10]

Informations[10]Castilian political theory further ascribed to royal authority a natural supremacy demanding its subjects' total submission on pain of death or blinding (Fuero Real). Not even his advisors may criticise the king (Libro de los Cien Capítulos). Alfonsine legal codes distinguished between the crime of lese-majesty, directed at the royal person and that more serious of treason directed at the monarchic power and thereby at the community. The destruction of the sovereign's effigy fell in the second category. Even though the texts still referred to royal power with the words real mayoría (“superiority”), a shift had taken place toward real majestad (“majesty” implying a particular kind of aura). Thus the idea of the king as incarnation of the state was gaining ground, meanwhile Philip the fair, one generation later was content to assert his growing authority without coming up with an exact theory. Only in the Coutumes du Beauvaisis (Philippe de Beaumanoir[11],1283) does one find anything about an absence of limitations to the royal power.

The conception of the kingdom as of a political body, drawn from St Paul (see his description of the church as the “body of Christ”) and from Aristotle (for whom the state had its source in human nature) was developed by John of Salisbury[12] in the 12th century. In Alfonso the Wise's Castile it helped legitimate the reinforcement of royal power. The king was “the soul and the wellspring of the people” in the “body” constituted by the kingdom, that is to say he pre-existed the people for he was its finality (Espéculo, Fuero Real). Thereafter, he was more simply considered like the head of the kingdom, itself likened to the body (pardidas). The idea of the kingdom-nation thus took precedence over that of the kingdom-territory in a modern conception foretelling the nation-state. The actual notion of monarchic state was ripening. The Libro de los cien capítulos indicates that the king and the kingdom are two persons but one single thing. Charters state that some revenues “belong to the kingdom”, not to the king. The term “crown” appeared in the year following Alfonso's death in 1285. The use of the body metaphor is more random in Philip the Fair's France. The pamphlet Rex Pacificus, for instance, sets forth a vision of society as a body the monarchy of which would be its heart and the church its soul, an argument developed in favour of the separation of powers. Jurists developed for their part the theory of the king's dual body, one taken by death and the other never dying making thus the distinction between the king as an individual and the crown as an institution.