The renewal of regard for mysticism, The example of the Carmelite studies 1920-1930

A greater visibility after the Great War

This social phenomenon which seemed to have been stamped out by the beginning of the 20th century, had a resurgence after the First World War. The 1920's, in fact, saw the proliferation of stigmatics: Marthe Robin (1921 - Drome)[1] , Marie Thérèse Noblet (1921- Ardennes)[2] ,Yvonne Beauvais (1922- Mayenne)[3] , Marie Rose Ferron (1925 – Québec), Therese Neumann (1927– Bavaria). This phenomenon coincided with a renewal of interest by academics in mysticism which went beyond medical and psychological circles [as is shown also in Part 1, Chapter 3 of this course]. In the university, the ethnographic works of Lucien Levy-Bruhl[4] and those in philosophy by Jean Baruzi[5] , as in certain Catholic circles (following the Dominicans in La Vie Spirituelle), the phenomena of the mystic life were reinterpreted. Overseas, the work of William James[6] also contributed to a real revival with regard to these subjects.

The Carmelite studies in the 1930's

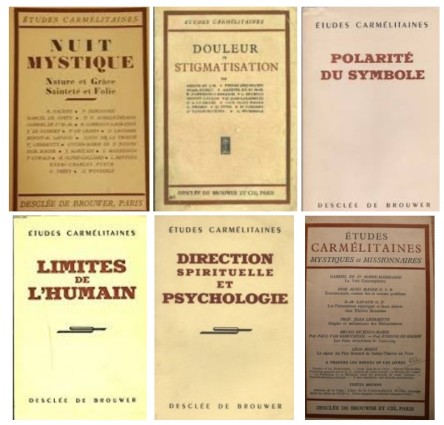

A sign of this development was the founding in 1931 by Bruno de Jésus Marie[7] of Les Études carmélitaines mystiques et missionaires following on from the creation of a pre-war review of mysticism (Études carmélitaines historiques et critiques sur les traditons, les privilèges et la mystique de l'Ordre). The idea of the founder was to encourage collaboration between doctors, psychologists, theologians and mystics. In its first issue he explicitly called for scientists who were keen to defend true mystics against spiritual counterfeits, specifically, to this end, from the psychological and psychiatric sciences. These were no longer considered as potential enemies, but on the contrary, as allies.

One of the objects was to then establish criteria acceptable to psychiatry and to spiritual advisers to distinguish the true mystic from the false. Thus the suspicions surrounding doubtful supernatural phenomena would not be able to tarnish the image of true mystics. Following the creation of the review the first workshops on religious psychology were organised and held at the Convent of Avon in 1935, bringing together Carmelites, Thomists and psychiatrists. From 1936 these workshops became an international institution. The reputation of these meetings attracted doctors from the Society of Saint-Luc[8] , the psychiatrists Henry Ey[9] and Jean Delay[10] , and psychoanalysts Charles Odier[11] , Georges Parchiminey[12] and Charles Henri Nodet[13] . This movement met the aspirations of a certain spiritualist tendency in psychiatry. Many Catholic doctors then in effect occupied a strong institutional position, including within L'Évolution psychiatrique[14] , a group which was re-evaluating the 'belief' of those suffering from hallucinations. Among them was Henri Ey, whose early theories were anchored in a desire to break the mechanisms of deterministic and materialist psychiatry which, for him, threatened to imprison all mystical theology.

The debate on the stigmatisation of Therese Neumann in the 1930's

The actors in this new network of discussion on mysticism latched on to the events which took place in the life of Therese Neumann (1898-1962) . The story may resemble those of the 19th century: a difficult childhood, an accident in 1918 followed by attacks of catalepsy, the beginning of a long life of suffering painted by hagiographers as a model of holiness and by the doctors as evidence of 'serious hysteria'. Then came the revelation, on the day of the beatification of Saint Theresa of Lisieux[15] in 1923: an apparition of voices announcing her speedy recovery. As Good Friday approached in 1926 Therese Neumann's eyes began to secrete blood, then stigmata appeared on her hands, feet, and forehead, sign of complete stigmatisation. From that time on she stopped eating.

The echoes of the stigmatisation of this Bavarian peasant woman at Konnersreuth[16] during the 1920s reached France at the beginning of the 1930's. French academics debated the issue from 1933 in an issue of Études carmélitaines, then through workshops on religious psychology in April 1936, and lastly in a special issue of Études carmélitaines given over to Douleur et stignatisation [Pain and stigmatisation] published in October 1936.

Beyond the controversy, the work of Études carmélitaines contributed to extracting the stigmatics from the field of miracles. After all, why should hysteria and holiness be mutually exclusive? This kind of interpretation was revisited a few months later in the analysis of the case of M-T Noblet (1938-1939). In a wholly Freudian interpretation, Roland Dalbiez[17] described this woman as a specialist in 'sudden recovery', seeking a secondary benefit of her illness. This is perhaps the point where the reconciling of mysticism and the new medical-psychological knowledge reached its limits. Father Bruno de Jésus-Marie had to gain the intercession of Agostino Gemelli[18] to obtain Papal permission to continue his intellectual adventure.