The evolution of the Sufi movement in the Maghreb

Three phases may be identified in the history of Sufism in the Maghreb: the phase of the Marabouts during which the mosque was transformed into a place of the teaching of mysticism, the phase of the Tawaifs during which the tribes sought to develop their holiness, and, lastly, that of the Zaouia when holiness led to power.

The Maribout phase

Sufism's arrival in Morocco coincided with that of Islam and the building of the first mosques aimed at persuading the Amazigh [Berber] tribes to adopt the principles of the new religion. These first Moroccan mosques, named after their founders such as Chakir Al Azdi, Oukbaa Al Fihri and others, were then transformed into places for the teaching and practice of mystical techniques but also for devotion to the saints of the past. The Amazigh tribes quickly adopted a strategy aimed at constructing a sacred genealogy, conscripting for themselves such and such a prestigious mystic in order to bolster their power.

Thus the Regragas[1] tribe developed its own foundation myth in which it was a originally Christian tribe, seven of whose members, or elders, were venerated as apostles due to their having met the Prophet Muhammed at Mecca; he converted them immediately before they returned to Morocco and converted the rest of the Regraras tribe and disseminated Islam in the neighbouring tribes. This same tribe then became the nursery for Sufism in the south of Morocco, opening the door to the creation and legitimation of a number of Sufi brotherhood and zaouias.

In parallel with the increasing prominence of the Regragas tribe, although not necessarily linked to it, the marabouts flourished in Morocco from the end of the 8thcentury (2nd century of the Hegira), building ribats occupied by marabouts known as 'Adorers of God' in the Sufi literature describing their lives. As in the East, these marabouts practised asceticism, renouncing luxury and the pleasures of life in the hope of enjoying them in Paradise. However, their way of life followed an independent and personal pathway. They practised in isolated places called ribats, which could be caves or huts in forests or mountains or on the banks of a river or on the coast. The important thing for these people was access to water and the means of nourishment. Although they lived apart from the world, these marabouts (murabits) played a role in framing social and religious rural life and thus contributed to the spread of Islam, of the Arab language and of religious study within the Amazigh tribes, while at the same time being in opposition to extremist trends in doctrine.

The marabout movement began to take form from the end of the 11th century (5th century of the Hegira), first in towns and then in the countryside. The generalised crisis experienced by Morocco with the passing of the Almoravid dynasty[2] at the end of the 12th century (6th century of the Hegira) brought about a reorganisation of the ribats under the aegis of the Al Ghazali[3] school, known in Morocco under the name of “the school for the consecration of Sufi unity”, which inaugurated a period of stability in Sufism.

Phase of the Tawaifs: or when the tribes sought to build their own sanctity

During the phase known as Sufism unity, when many of the different currents of Sufism converged, a number of major questions remained. The first concerned the meaning and nature of spiritual states for the Sufis (Al Ahwals), the second concerned the stages to be gone through before reaching the final supreme state (Al Maqamats). This was the era of the appearance of the Sufi taifas[4] , often described in accounts of the time. These groups were built on tribal bases and became authentic institutions which developed collective practice of mysticism. These taifas were distinguished by the geographical origins of their followers and did not always adopt the same practices in spite of the convergences which have been seen. Their flourishing nevertheless demonstrates the richness of Sufism at this time.

From then on the leaders of the Sufi taifas enjoyed an authority unprecedented in the history of Morocco. Due to their tribal base, they became major actors in the re-establishment of order and security and played an intermediary role between the tribes and the central government. The dynamism of the taifas, coupled with their hold on the people, allowed for the propagation of Sufi principles throughout almost all of Morocco, leading to the birth of popular Sufism or Sufism of the brotherhoods.

Cycle of the Zaouias: or when sanctity leads to power

The Merinids, in power between the 13th and 15th centuries, attempted, without success, to hinder the development of Sufism. On the contrary, each time the Moroccan centre of power suffered a reverse, Sufism became stronger. In this way, the Sufi movement gave birth to the Zaouias, religious bodies which were a product of a long process of Moroccan Sufism since the 10th century (4th century of the Hegira) and its political and spiritual growth under the Almoravids.

The process by which this originally religious and mystical institution came to build for itself a political destiny is called by historians the “cycle of the Zaouia”. The success of the Zaouia “inevitably cast a shadow on temporal power, which saw the monopoly of religious authority slip from its hands,” as the historian Paul Pascon writes. The history of the Zaouias is therefore closely linked to that of the ruling dynasties of Morocco. In some cases the Zaouias embodied the foundations of political authority, because of the prominent political role played by their leaders. Thus the leaders of the Zaouias arbitrated and put an end to factional conflicts, because “the tribe [was] incapable of producing institutions to surpass [them]” (Paul Pascon). For many, the Zaouia was the court of the tribal nations, inasmuch as the tribes recognised them and, in a segmented society such as that of Morocco, where the tribe was a vital component, the Zaouias played an essential role in guaranteeing its stability.

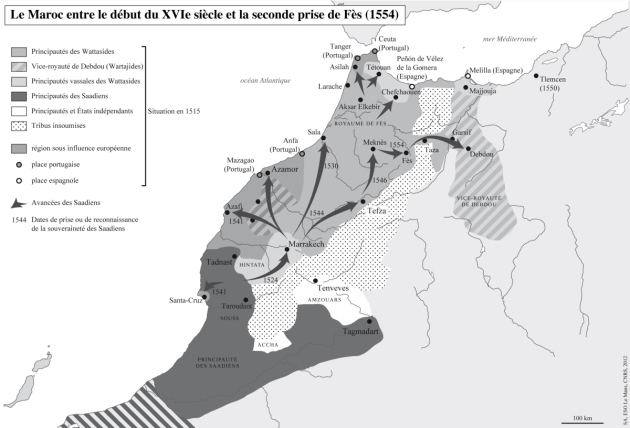

When Morocco[5] was once again plunged into crisis at the beginning of the 16th century (10th century of the Hegira), the Zaouia was seen as a fundamental institution, not just as a religious or educational body, but as a decisive political instrument.

Thus contemporary historians have emphasised the major role played by the Jazouli Zaouia18 of Sous, in particular its two principal leaders: Mohamed Ben Moubarak, head of the Zaouia of Aqqa, and Baraka ben Ali, head of the Zaouia of TiTidssi, in supporting the Saadians through active propaganda in their favour in the whole of southern Morocco, and amongst the disciples of the Jazoulite Zaouia scattered throughout the regions of the country, until their investiture in power in 1554. The zaouias also campaigned in the rural areas under the control of the Saadians which were beset by famine and repeated droughts. In this way the Jazoulis gave strong support to the Saadians in their conflict with the central power of the Wattassids[6] (Banou Wattas).

The grand sheikh of the Jazouli brotherhood, Abdallah al-Ghazouani[7] , dropped his allegiance to the Wattassids in order to give official support to the Saadians when they entered Marrakesh in 1524. He then became the chief mover of the movement, directing military action against the Wattassids and organising his disciples to tackle the consequences of the crisis in the countryside. Thus he cemented the project of the first Jazouli marabouts to, for one part, legitimise the brotherhood and, for the other, to put in place a political model capable of unifying Moroccans in their fight against the Iberians. Thus the nation state of Morocco founded by the Saadians rested on moral principles largely inspired by the mystical doctrine of the Jazouli brotherhood.