Theodoret of Cyrus (c 393-469) (vers 393-468)

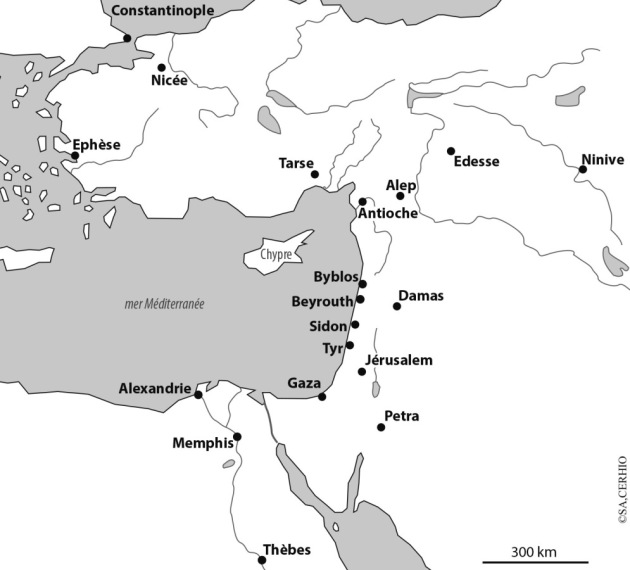

Theodoret of Cyrus was born in Antioch where he had his education. In 423 he was elected as bishop of the town of Cyrus in the north of Syria. He accepted the post without seeking it, and worked on the development of the town, where he helped to finance the building of an aqueduct. He engaged actively in the life of the Church. Early on he fought against paganism and heresy and took part in the debates on theological questions in the great ecumenical councils at Ephesus[1] in 431 and Chalcedon[2] in 451.

He opposed the monophysite doctrine[3] promoted by the school of Alexandria and rejected the thought and procedures of its teachers, in particular Cyril[4] and Dioscorus[5] . He was condemned and deposed at the 'Robber synod' of Ephesus[6] in 449. For a long time he remained an emblematic figure of the Council of Chalcedon; when the Emperor Justinian[7] wished to conciliate the monophysites, he did not hesitate to condemn certain of Theodoret's ideas at the second Council of Constantinople in 553[8] , also known as the Council of the Three Chapters. This assault on his person did not succeed in ruining his intellectual reputation, which remained considerable.

The Religious History, published in about 444, in other words the history of the monks/nuns we are studying here, is only a minor part of his body of work which, at the time, was much less influential than the Life of St Anthony by Saint Athanasius[9] . However, the work constitutes an irreplaceable source on the history of Christian life in northern Syria due to the events it recounts and the personal witness of Theodoret. The work is a collection of thirty biographical accounts, each under the title of the ascetic represented. These are augmented by a group of ecclesiastics and lay people, whose inclusion enriches the prosopography of the work and brings the total number of ascetics and cenobites to sixty-two. Theodoret presents founders and great teachers such as Saint Maron, founder of the Maronites, deceased before his accession to the episcopate in 423, and Simon Stylites (XXVI), who survived until 459 and whose life was related in about 444.

The geographical coverage of the work is vast: northern Syria with its divisions and expanse including Antioch, Chalcedon and Apamea, part of the Euphrates with Osrohenia and Cyrrhus, “the regions extending from the Gulf of Cilicia to Edessa in Mesopotamia, and from Cyrrhus to Apamae”. He underlined the Mesopotamian influence in Syria. At the same time the influence went beyond this grouping to Phoenicia, where there was a community organised by Abraham, future Bishop of Carrhes cultivating the Lord's vineyard in a village in Lebanon. This was the southernmost extent of Theodoret's geography. Specialists in the history of monachism in the 20th century such as P. Festugière, A.Vööbus and P. Canivet have translated, edited, commented on, evaluated and rehabilitated his work.

In writing his history, Theodoret invokes two motifs: to maintain the memory of the great ascetics and save them from being forgotten, and to edify future generations. Theodoret was particularly well placed to undertake this work. His family had always visited ascetics to make offerings. He himself had visited them from a very early age, being himself a miracle child[10]. Thus he renounced a rich patrimony to experience the life of a cenobite in one of two monasteries in Nikertai, near Apamea, between 413 and 416, far from his birthplace. After he became Bishop of Cyrus in 423, he remained nostalgic for that peaceful life of prayer and study. After he was deposed in 449 by the 'Robber synod' of Ephesus, he obtained imperial permission to return to his monastery at Apamea.

His maternal language was Syriac, but he mastered Greek and was fully conversant with classical culture, which is reflected in his process and stylistic approach. He was therefore very well placed to gather information, express it and promulgate it through his work.

Theodoret mastered the literary genre of biography of prominent men and was also well versed in Egyptian monachism. However, he used the traditional process of biography and eulogy in an original way, additionally deploying “the little everyday facts rooted in the soil of his country|”, as Pierre Caniver points out. Thus he presented to his readers typical models of the Christian life.

While his portraits are essentially of men, Theodoret dedicates three of his 'notes' to women, Marana and Cyra , and Domnina .

The first two were from Beroea, modern Aleppo, where they ran a settlement at the entrance to the town and lived life in the open air, without any protection from the weather. They received visitors only from women at Pentecost, and passed their time in works of asceticism. They wore iron chains on their bodies, prayed continuously and practised fasting on the model of Moses and David. Their penitences were such that the bishop visited them and recommended prudence and moderation. Unusually for the period, Marana and Cyra went on pilgrimage to the Holy Places of Jerusalem and on their return, visited the tomb of Saint Thecla. For her part, Domnina imitated the way of life of Saint Maron[11] and built a little cabin in her mother's garden. She engaged in the same spiritual struggle and accomplished the same ascetic works. She dedicated her time to singing hymns, spinning and immersing herself in uninterrupted contemplation.

The struggle of these female recluses surpassed that of men. They were not the only ones to lead this life. Theodoret counted more than 250 who lived in the same manner. If they chose to live in the open air like solitary hermits, it was to acquire superior virtue[12] , that is, union with the Bridegroom; the convent, a place of communal life, was made fro the practice of ordinary virtues[13] .