The emergence of a Jewish art in late antiquity

The destruction of the temple in the year 70 of the Christian era was a major upheaval for Jewish society. Nevertheless, the Jewish presence robustly held up throughout antiquity's ultimate centuries. Synagogues[1] gradually became a significant locus of Jewish worship. It was not the presence of the Torah scrolls alone that made holy sites of them but also their structure and art. This art exhibits three novelties. The first is the introduction of the human figure, signalling the transgression of the aniconic prohibition. The second is the reliance of its iconography on the incorporation of themes that made sense both in Jewish and non-Jewish cultures, the third is the presence of eagles, symbols of the Roman authority, at the entrance of the synagogues. The Roman-Byzantine period is thus marked by the emergence not so much of figurative art among the Jews than of a specifically Jewish figurative art. The synagogues at Beit Alpha, Dura Europos, Ein Gedi, Gerasa, Ma'on, Na'aran, Susiyah bear witness to this rich ornamentation consisting of frescoes and mosaics. The iconography of these Jewish places of worship drew on a threefold thematics.

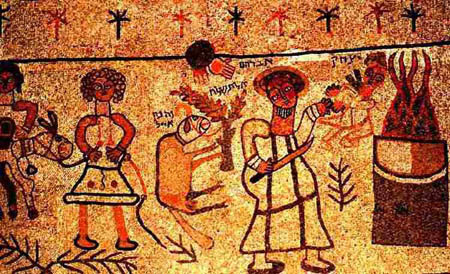

A Jewish source comprising Jewish ritual objects (menorah, lulav[2], ethrog[3] and shofar[4]). Such details are frequently to be found on everyday utensils, namely glassware, lamps and also sarcophagi. The mosaics in synagogues show biblical scenes such as Noah's Ark, in Gerasa and Daniel in the Lions' Den, at Susiyah or the Sacrifice of Isaac at Beit Alpha.

A non-Jewish source including lions at the entrance, the zodiac[5] and the Sol invictus[6] at the centre and the personification of the seasons[7] at each corner. In terms of content, these themes are not specifically Jewish but they are hardly ever found elsewhere.

A non-Jewish source comprising animals, vegetation and some Nilotic scenes[8] reproduced throughout the Empire.

Informations[9]

Informations[9]Human figuration was extant but not so frequent. For instance on the En Gedi mosaic, the zodiac figures are set off with birds at each corner instead of the Seasons. It carries four inscriptions two of which are in Hebrew[10] and two in Aramaic[11]; they mention community benefactors. The Lod Mosaic displays similar concerns. There again the zodiac figures alongside animals and on the lower register, two ships. Though the evolution is patent, it is difficult to grasp its mechanism. Judaism, shaken by the destruction of the Temple did go through transformations the deeper for accommodating vastly different trends. And they are particularly difficult to identify in the archaeological documentation as they were fast evolving while their doctrinal framework had yet to be fixed. The multifarious diversity of representation is an indication of the degree to which these images seem devoid of any fixed iconographic code and difficult to set within a well-defined doctrinal code. The synagogues where these mosaics have been discovered do not appear to belong with Rabbinic Judaism[12]. The orientation, the positioning of the entrances and the profusion of forbidden images – such as menorot and gods holding sceptres and orbs[13] – are in clear defiance of rabbinic rules. The possibility that some may have come under exegetic scrutiny may perhaps not be altogether excluded anymore than that others may have gone unnoticed or indeed been rejected by some local worthy.

It remains however more likely that these synagogues sided with Hellenistic Judaism[14].

Rabbinic Judaism was not indifferent to the allure of imagery. The question of the acceptation of images actually represents one of the most significant subjects addressed by Talmudic literature, notably in the treatise Aboda Sarah, which deals with the question of idolatry. It shows the effort made to distinguish between images with a religious purpose – that are ipso facto prohibited – and those with an aesthetic role - which the rabbis themselves have no qualms using. They were accepted as long as they did not touch on rites, for instance in funerary monuments. The catacombs at Beit Shearim offer an idea of this new relation to representation marked by Hellenism in that it is the burial site of rabbis among whom possibly, the most famous: Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi[15]. The ossuaries are mostly adorned with pagan scenes, such as Leda and the Swan, the Greeks' fight against the Amazons[16] or even a bearded head, which could pass for that of Zeus but without certainty. Most of the inscriptions engraved on the ossuaries are written in Greek (218 out of 250 instances) – the others are in Hebrew or in Aramaic. The epitaphs evoke the high figures of Greek mythology in the finest Homeric style[17].

Informations[18]

Informations[18]The attitude to the prohibition evolved over time and indeed according to the social groups concerned. The aniconic prohibition appeared in the 7th century BEC, at the term of the process that ensured the passage from pagan polytheism to Jewish monotheism. The First Temple, which housed the statue of YHWH, was destroyed in 587 but a few decades later in 516, the building of the Second Temple opens a period of several centuries characterised by the strict observance of the aniconic prohibition. Hellenic pressure, the end of political independence and the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE brought about mutations within Judaism whereby it adopted a more tolerant approach to images in everyday life. However a rift may be observed between the Jews who call upon images within the rites and those who object to it most strenuously. Meanwhile, the proliferation of images seems to cease as from the 8th century – that is at the time of the Iconoclastic crisis in societies under Christian authority and of the rejection of figurative imagery in societies under Muslim authority.