The Cistercian rejection of figurative representation

No reflexion on the theoretical discourse held by the Cistercian movement can make the economy of the perusal of its most prolific author and figurehead Bernard of Clairvaux[1]. The Apology to William of Saint-Thierry, written towards 1124-1125 represents the wellspring of the thinking about Cistercian aniconism. There, he stigmatised as “disorders” “impossible to overlook” what he saw as too imposing a size and too abundant a decoration in his times' religious buildings, recalling “the ancient ways of the Jews' synagogue”, referring to “idols” and warning against the “idolatry” caused thereby. A famous passage fustigates the representations of fantastic beings in the cloisters and can be construed as a rejection of Romanesque sculpture as practiced in his days within traditional monasteries such as that in Moissac, and more specifically a rejection of figurative imagery.

Informations[2]

Informations[2]Other Cistercian authors would follow suite in the 12th century. Aelred of Rievaulx[3], in The Mirror of Charity, a treatise he wrote in 1142-1143 at Bernard of Clairvaux' request, castigated the taste the “lustful” showed for paintings and sculptures as a sort of “covetousness of the eyes” and proposed that the ideal church would be one where the worshiper would “find neither painting nor sculpture, nor anything precious, no carpet-lined marble, no wall hangings where the history of the peoples might figure, kings' battles, or indeed some Biblical scene”. Circa 1160-1162, in his Formation of Anchoresses he warned pious women against the presence in their cells of paintings, sculptures and tapestries (particularly those drawn from the bestiary). About mid-12th century, another Cistercian, Idung of Prüfening[4], reproached the Cluniacs[5], in his Dialogue between Two Monks, with their taste for paintings and low-reliefs, colourful tapestries and stained glass windows, branded by him a “concupiscence of the eyes”.

The same preconceptions pervaded the normative texts of the Cistercian order. In 1119, in the statutes annexed to the Exordium Cistercii, the Cistercians banned sculptures and paintings from their churches. Throughout the years 1120 to 1147, the General Chapter of Cîteaux[6] restated these prohibitions and further decided to proscribe all forms of figuration, and to restrict the use of colour in the order's illuminations and stained glass. This opposition to imagery was to endure, as the statutes of the General Chapter reiterated the prohibition some twelve times up to the years 1330.

On the surface, the Cistercian material legacy appears to suggest that these norms were scrupulously adhered to. The classical Romanesque figure-laden capital was banished and superseded by plant-inspired capitals of the utmost simplicity, notably the famous ‘water leaf'.

Informations[7]

Informations[7]In some cases, for instance in the abbeys of Le Thoronet or Sénanque, the very choice of architectural structures was dictated by the willed avoidance of any call for capitals or surfaces liable to decoration. There are no 12th century Cistercian figurative wall paintings to be found.

Informations[8]

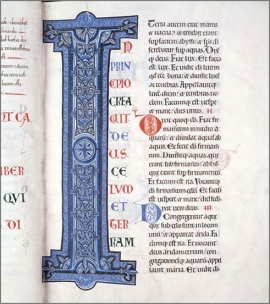

Informations[8]In the field of miniature, the Cistercians developed a sophisticated non-figurative monochrome style the aesthetics of which were fully in keeping with the rules. In their windows, 12th century Cistercian abbeys seem to have systematically resorted to grisaille glass, patterned only by the geometric tracings of the lead cames. The paving tiles remained plain or boasted geometric or plant patterns.

Informations[9]

Informations[9]The lay out of the windows and architectural components, often observing a ternary rhythm aimed to bring the divinity to mind in a symbolic manner through a Trinitarian evocation, especially in the most conspicuous points in the abbey, notably the apse, behind the high altar.

Informations[10]

Informations[10]