The Indigenous gods in the reorganisation of Roman Gaul's territories

The most important restructuring of the Gaulish territories after their conquest was conducted during the Augustan age: the redefining of provincial boundaries and allocation of new legal status to the urban centres, backed up by the deployment of a road network easing the liaison between the new power hubs secured for Rome a tighter control of the provinces[1]. In order to advance the provincial populations' acceptance of these major upheavals, Rome relied partly on new religious structures and partly on the old ones, effecting a large-scale overhaul of the provinces' « religious landscape »

.

Instigated by Drusus[2], the imperial cult introduced as early as 12 BC made for an entirely novel feature in the provincials' religious landscape. Hitherto, there had not been in Gaul any national pantheon nor indeed any pan Celtic cult but a multiplicity of indigenous gods locally honoured in their separate communities. Now, in the framework of the build-up to his German campaign, Drusus had an altar built in Lyons on grounds neighbouring the Roman colony promoted federal capital for the purpose, and invited representatives from all of Gaul's civitates[3] to come and celebrate a cult. The creation of this cult site afforded the first occasion for the delegates from those communities to assemble for the joint celebration of a cult dedicated to Rome and to Emperor Augustus[4]. The object of this initiative was to demonstrate the provincials' loyalty towards Roman power against a background corroded by preparations towards the conquest of Germany. Epigraphic and iconographic documents provided by the site confirm that all of Gaul's civitates were represented, including those from Narbonensian Gaul, such as Arles or Glanum but excluding those from the left bank of the Rhine. As from 9 BC, the latter had the benefit of an imperial cult altar at Ara Ubiorum (present day Cologne). Thus the Roman power had the clear intention to make of its provincial elites the living expression of the fidelity owed the emperor whose legitimacy and might were warranted by his divine aura. The civitates and their representative's autonomy was no longer conceivable without this expression of loyalty to Rome and to the emperor; conversely, these new power centres were henceforward to enjoy the divine protection of Roman power as honoured through its divinities.

Informations[5]

Informations[5]Droit : CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F(ilius) PATER PATRIAE

Revers : Autel de Lyon; ROM(ae) ET AUG(usto)

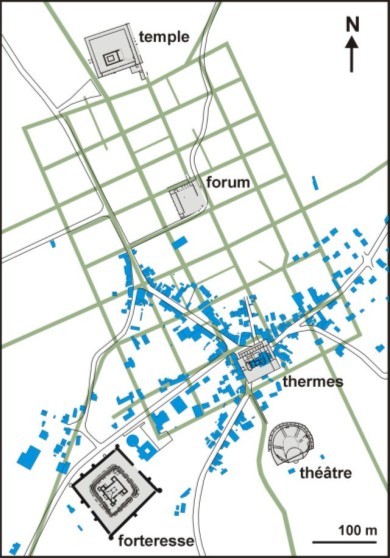

The territorial restructuring went hand in hand with a broad urbanisation movement. Begun earlier in Narbonensian Gaul with the colonial settlements initiated by Caesar[6] in the Rhone valley, it became widespread. Many factors impacted on the choice of the sites taken up by the new capitals: economic potential, accessibility but also sometimes their divine potential too. In several instances, the new capitals benefited from the divine aura from indigenous cult sites. In Glanum, the new capital of the Glanics' civitas, the oppidum latinum went in the Augustan age through a redevelopment of its public buildings which saw the monumentalization of the cult site dedicated to the god Glanis[7]. In Nimes, the capital of the Latin colony[8] preserved the name of its local divinity Nemausus honoured in a sanctuary thoroughly overhauled under Augustus. In the middle of the first century, the construction of a monumental sanctuary on the probable site of an indigenous cult consecrated the choice of Jublains as civitas-capital of the Diablintes after they were granted Latin rights. Hard by the towns of Autun, Meaux, Le Mans Corseul, Trier, great monumental sanctuaries perpetuated indigenous cult sites and ensured the divine protection of the capitals and restructured territories. On this basis a productive dialogue developed between indigenous traditions and the innovations the Roman power wished to introduce, one which is also observable in the distribution of cult sites in the townscape.

Urban centres were thus taken up mostly by religious buildings – altars or temples – dedicated to divinities from the Roman pantheon or erected in the honour of the imperial family's dead. The administration of Gallo-Roman civitates, entrusted to a local senate[10], could only be conducted autonomously through the recognition of Roman power as represented by its divinities: the public square of the capitals, where the senate met, must accordingly set close together a meeting place and a building where the cult owed to the Roman divinities could be performed. This grouping finds a lucid illustration in the forum at Nimes where the curia, the senate's meeting place, stands opposite to the temple, known as the Maison Carrée, erected in memory of Augustus' grandsons prematurely dead after the emperor had made them his adoptive sons and heirs. Some civitates pergrinae[11] to whom no religious obligation applied, also adopted the imperial cult, ingratiating themselves before the Roman authority – whose citizen were in a position to hope for advancement of their legal status: this phenomenon is attested by the presence, right from the Augustan age, of priests of Rome and Augustus in civitates peregrinae such as Rodez, or by the adoption of a tripartite forum one of the short sides of which was dedicated to a roman style monumental temple, like in Feurs. With this model, the monuments dedicated to indigenous divinities seem excluded from the city centre and restricted to its periphery, within or without the walls. Nevertheless, the case of Trier with the Altbachtal and Avenches with the Grange des Dimes sector show that their eccentric situation did not stop these sanctuaries from holding out as major hubs well attended and enjoying ongoing monumentalization.

Starting with the Augustan age, Gallo-Roman populations faced the complete redefining of their religious structures. The setting up of an official religion, complete with new monuments and a new priesthood overturned the hierarchy of indigenous divinities and subjected the new civitates to the authority of Rome's gods. The might of indigenous divinities did not vanish but was sucked into that redefining process leading to the emergence of a new pantheon.