Apollo, god of victory: from the Second Punic War to the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul

During the second Punic war, after the disasters at Lake Trasimene in 217 and at Cannae in 216, Rome's ruling class implemented a range of operations of a cultural and religious nature aimed at restoring the pax deorum[1] considered requisite to a victory over Hannibal[2]. Newly introduced or more ancient divinities considered propitiatory to victory, such as Concordia or Sicily's Venus Erycina, were pressed into service. And so it was with Apollo when, in 216, after the Cannae rout it was decided to send Quintus Fabius Pictor[3] to Delphi there to consult the god's oracle. In her answer the Pythia[4], having specified the gods and goddesses to whom supplications must be addressed, clearly stated that subject to the Romans' observance of these ritual prescriptions, « the victory in the war will be belong to the people of Rome »

. A few years later in 212, another oracle, an Italic one for good measure (viz. the Carmina Marciana or Marcian prophecies), stated « Romans, if you wish to expel the enemy, and [lance] the ulcer which has come from afar, I direct, that games be vowed to Apollo, and that they be performed in honour of that deity, every year, with cheerfulness. »

Accordingly, as from 212, Ludi Apollinares were celebrated on a yearly basis. In both oracles, the wording leaves no doubt as to the correlation between the god's intervention and the granting of victory. Likewise a legend that may hark back to the 2nd century BC reports that during the celebration of the games in 211, miraculous arrows put the Carthaginian enemy to flight at the gates of Rome. For their part, Livy (XXV,12,15) and Macrobius[5] (Saturnalia, I, 17, 27) stress the fact that the games were established « in order to secure victory, not public health. »

To be sure the god who harries with his arrows an enemy the Italic oracle compares to an ulcer, or – depending on translations – to a plague is still the Iliad's archaic god who indifferently deals out death or health as was the Apollo Medicus to whom a temple was dedicated in the 5th century BC. However starting with the second Punic War, his tutelary power of granting victory became increasingly dominant. That god is undoubtedly the Pythian Apollo, the Delphian god who, according to legend gained possession of his sanctuary after his victory over Python the serpent who had custody of the place. Upon his victory Apollo was given laurel branches and so the god is represented with a laurel branch or crowned with the laurels that consecrated his victory. Conveniently, the relation to the Delphic sanctuary and the triumphs of Roman imperatores[6] were two features that would mutually reinforce the Pythian god and the 2nd century Roman ruling class in relation to each other.

In 215, upon his return from his mission in Delphi, Quintus Fabius Pictor placed on Apollo's altar in the Prata Flaminia the laurel branch and crown he had worn to consult the oracle and to perform sacrifices. It is well known that the crown of laurels was also worn by victorious Roman generals at the celebration of their triumph. For all that the Roman triumph ceremony does not stem from the cult of Apollo, at some stage the affinities extant between the triumphal procession and its associated symbolisms and the celebrations of Apollo's worship were noted. In Delphi, laurel had a purifying function; likewise, according to jurist Masurius Sabinus[7], triumphal laurel was meant to cleanse the army returning from a campaign from the pollution of spilled blood. Triumphal processions incidentally set off from the Campus Martius where the temple of Apollo was sited. These analogies, these similarities may well have struck a chord with Roman ruling class thinking, especially at the beginning of the 2nd century BC. At that time the Delphi sanctuary was the recipient of offerings from victorious Roman generals: Titus Flamininus[8] dedicated some silver shields and a gold crown circa 190. Scipio Africanus[9], soon to be honoured by the Delphians, had dedicated to the Delphic god a part of the spoils from his 206 Spanish victory.

At the beginning of the 2nd century, Apollo's sanctuary in Delphi was perceived in the collective mindscape as the locus of the defence of Greek civilisation against « barbarian »

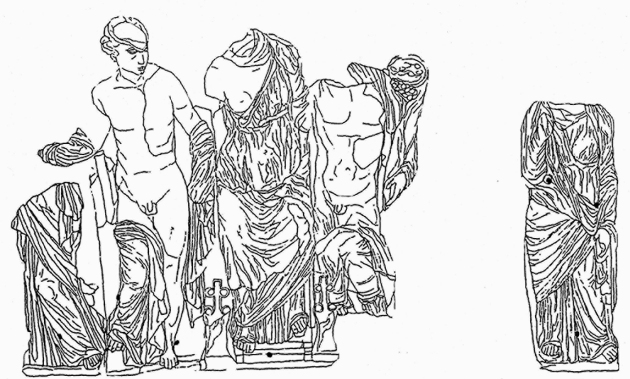

invaders thus providing Rome's ruling elites with a choice propaganda theme. It so happens that in 279 BC a band of Celtic raiders, who would become known as Galatians, had attacked the sanctuary. According to legend, the defence of the holy place had been ensured by the gods themselves: Apollo allegedly appeared in full epiphany, the thunder struck, the earth quaked. The victory of Delphi's god against the Galatian raiders stood as a symbol of victorious struggles against the barbarian enemy. An iconographic echo of the Delphic sanctuary myth as symbol of the victorious struggle against Barbarian invaders can be found in a statue of Apollo trampling a Galatian shield; found in Delos[10] it is consistent with the statuary of Apollo Lykeios[11] as honoured in Delphi under this epiclesis.

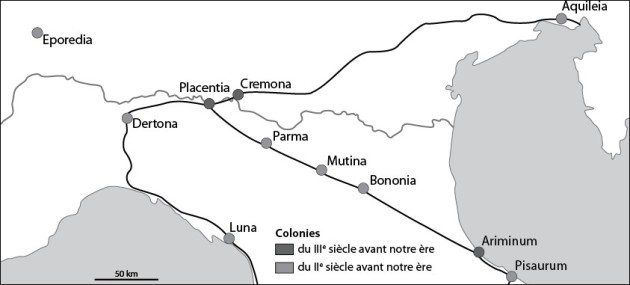

The propaganda models that had served in the Greek world were thus redeployed by Rome during the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul against the enemy of old, the Celtic peoples. Significantly, Greek historian Polybius[12] ends the excursus of book II (35,7) of his Histories, in which he describes the wars Rome lead against the Gauls in Italy in the 4th- 3rd centuries, with a reference to the Greeks' wars against the Persians and the Galatians. Accordingly, as they established new colonies in Cisalpine Gaul, the representatives of Rome's elites had Apollo's effigy feature in the temples' pediments and in cult statues. In Luni, Apollo and Diana-Luna figure on the terra cotta pediment of the great temple erected in the early days of that 177 BC colony. In Piacenza (founded 218, reinforced 190) a three metre high statue in Greek marble has been found. Other representation of the god can also be sited at Cremona (founded at the same time as Piacenza), in Rimini and Aquileia ( colonies respectively founded in 268 and 181 BC). The statuary archetype for these representations is the so-called Cyrene Apollo, a variation on the Lycian Apollo created by Attic sculptor Timarchides. Now he was also the author of the statue for Rome's temple to Apollo Medicus in the Prata Flaminia which had been refurbished during the censorship[13] of e Marcus Fulvius Nobilior[14] and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus[15], the latter being one of Luni's founding fathers in 177. It is thus likely that the City's cult statue served as a model for the temple pediment of the colony.