Fakhr al-Din between revolt and loyalty

Fakhr al-Din is a scion of the Arab house of Ma'an who came from the Eastern part of the Abbasid empire and whose dominance over the Druze community had started with its settling of the Wadi al Taym, then the Chouf mountain around 1120. By the 15th century they had set up their centre of power in Deir al-Qamar, whence to stand up to the Ottoman authority. The Porte launched several military expeditions against the rebels. One such, led by Ibrahim Pacha[1], governor of Egypt in 1584, lay the country waste. Emir Qorqmaz[2] was not able to withstand the onslaught and was killed. His sons, Fakhr al-Din and Yunus[3], still children, were kept by their mother out of the way of Turkish retaliations ; according to al-Douaihy[4]'s records, they were entrusted to their uncle Sayf al-Din al Tanhuki[5]. When he reached 18, in 1590, Fakhr al-Din took over the running of the Chouf. His authority was soon to stretch from the Anti-Lebanon Mountains to the sea.

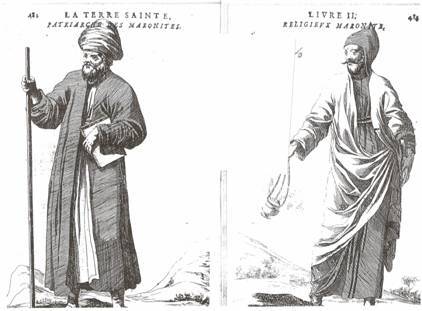

The mainly rural population fell into two distinct social categories: peasantry and aristocracy. The latter were the emir, the muqaddam[6] and the Sheikhs[7]. The peasant farmer's bound to his master was tight, particularly among the Druze. Two factions vied with each other for the exercise of power: the Kayssiyya[8], lead by the Ma'ans and the Yamaniyya[9]. These factions transcended confessional obedience but religious communities were no less a structuring agent of private and collective life: religion played a foremost role when it came to customs, traditions, behaviour, dress and language. The communities were lead by ulama[10], uqqal[11], patriarchs[12] and bishops[13] whose religious authority strayed into the political realm and who prevailed in the social sphere. They enjoyed a special status bolstered by strong traditions and the hazards of a geography that kept the Ottoman power at bay.

Under the sultanate of Selim II[15] and his immediate successors, the region was divided into three vilayets: Aleppo, Damascus and Tripoli. The emirate was boxed in the latter two, introducing a conflict between the authority instituted by Constantinople and the authority supported by the local populations. The young Fakhr al-Din provided security in the whole emirate by granting all Christians equality with the Druze, Sunni and Shia. He practised religious tolerance towards every community. Though belonging to a Druze community strongly attached to land as a guarantee of its perpetuation and jealous of its autonomy from any political or military power, he had no qualms in choosing Sunni and Maronites advisers. His biographer Ahmad al-Khalidi al-Safadi goes out of his way to show that the emir was a pious man, who « obeys God and the Sultan »

: he offered precious gifts to influential figures at court, to ministers as well as to the pashas of Damascus, Aleppo and Egypt. This enabled him to establish his authority and to eliminate his opponents but it did not quite shield him from « jealousy » or from manoeuvres aimed at isolating him from the governor of Damascus or from the centre of power in Constantinople.

In the event, Fakhr al-Din did not discontinue his predecessors' policies but altered some of the means to that end. He showed prepared to seek from European powers the military and economical support he needed to enlarge his territory and lay the basis for a sovereign political entity. In 1613, hard-pressed by the Ottomans, he called an assembly of dignitaries in Damour and, having found that any military resistance was impossible, he decided to withdraw from the situation by sailing to Europe. On his return in 1618, the wars the Ottoman sultans had engaged in the Balkans on the one hand and in Persia against shah Abbas I[16] on the other enabled the Emir to impose his authority on the regions neighbouring the Chouf under the pretence of ridding the country of its brigands. After his victory over the Pasha of Damsacus at Anjar in the Bekaa valley, his territory encompassed Antioch to the North, Palmyra to the east and Gaza to the South.