Mandalas and mountains

Japan has witnessed one particular evolution of the use of mandalas. It appears to be unique to that country and offers an excellent illustration of the way in which mandalas are understood by practitioners. In all the countries it has reached, Buddhism has shown a marked preference for religious practice in forests or mountains and several highly influential scriptures single out that environment as the best suited to spiritual realisation. Given the Japanese wealth of forests and mountains, this notion found a very receptive audience and was exploited in a particularly distinctive way from the 8th century on. This understanding of mountainous spaces grafted itself on a great many autochthonous beliefs and practices wherein mountains are a separate realm, astride the world of humans and that of kami[1] and buddhas. These “other words[2]” are often perceived and represented as Buddhist paradises and hells. Conversely, at times, mandalas too get projected onto mountains, or indeed the whole of Japan. Projections of this kind, which can be very detailed, figure ritualised itineraries as developed in Shugendō[3], a religious movement strongly influenced by esoteric Buddhism. This tradition's specificity is its focus on ascetic practice in the mountains.

The development of Shugendō, the doctrines and rites of which rely for the most part on esoteric Buddhism is also symptomatic of the considerable hold that particular Buddhist culture had on Japanese society between the end of the classical period and the beginning of the mediaeval period (11th-14th centuries). This period is marked by a pronounced ritualization in all aspects of life (political, religious, private), and by the conviction that Buddhism's Ultimate Reality is at one with the human world. In political terms, this conviction gets translated in the expression “the sovereign's law is the Buddha's law” (ōbō buppō): Buddhism champions Japan as Japan champions Buddhism.

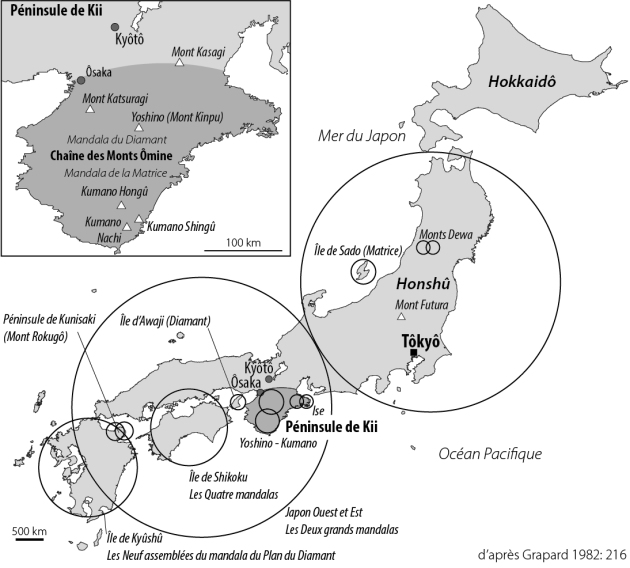

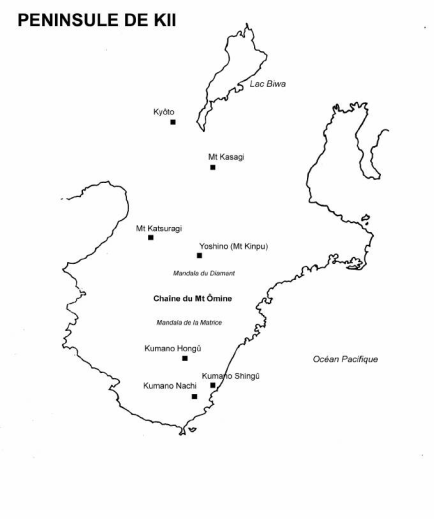

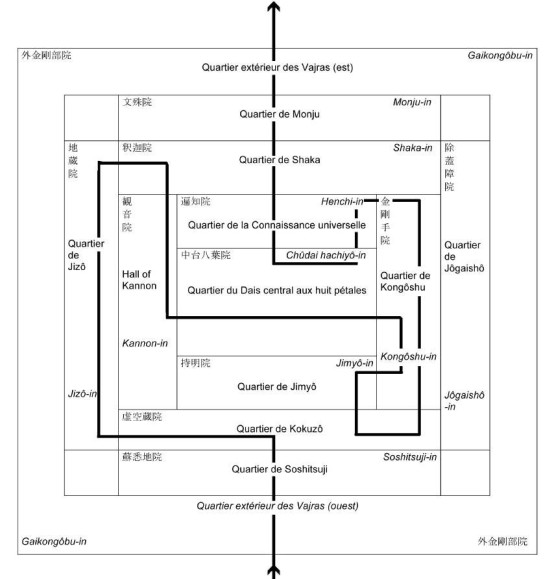

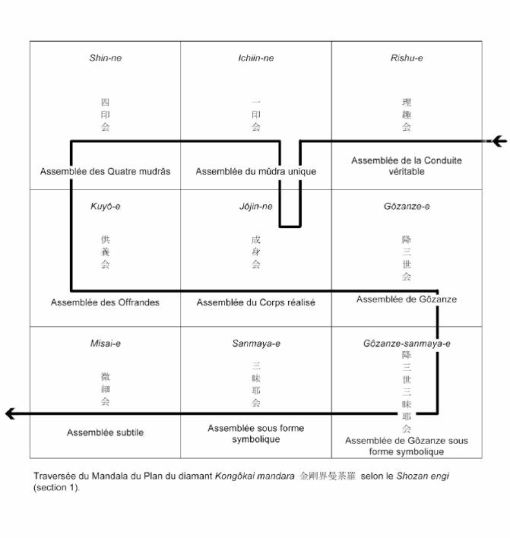

For instance, two 12th century Shugendō documents describe a progression both spiritual and geographic by means of a simultaneous journey through a given mountain range on the one hand, and the Mandala of the two Worlds on the other hand. Shozan engi (Origins of various mountains, 1193 ?) and Daibodaisantō engi (Origins of Mount Daibodai, 1155 ?) are two compilations of traditions and legends linked to ascetic mountain practice. Practitioners follow an itinerary the successive steps of which are, at the same time, the deities in the mandalas of the Womb and Diamond Realms, and the peaks of the Ōmine mountain range in the Kii Peninsula, in central Japan. The summits are named after the mandala deities they manifest, as well as being their dwelling place. Thus, the virtual cartography leading to Buddhist enlightenment as presented by the mandalas takes on an eminently concrete shape.

Along an almost vertical line from north to south, the Ōmine Mountain range dots the centre of the Kii Peninsula with a sequence of peaks rising to near 2000 meters that can be joined following the ridgeline. Mount Ōmine, nowadays called Sanjōgatake (1719 m), rises at around one third of the way down from the North. In ancient Japan, Ōmine referred to the whole mountain range. Because of its high peaks and its impenetrability, Ōmine is historically the most prestigious and hallowed region in terms of religious mountain practice in Japan. The string of places described in the two documents outlines a double course both through the Ōmine peaks and through the two mandalas thus projecting a virtual realm onto a real space. The peaks are spread over more than 120 kilometres, yielding a large-scale projection. The stages on the practitioner's itinerary are matched up with diverse parts of the mandala. Accordingly, the practitioner's progress whether across the mountain or the mandala becomes (ideally) a physical experience of non-duality, a temporal entrance into a realm of cosmic dimension.

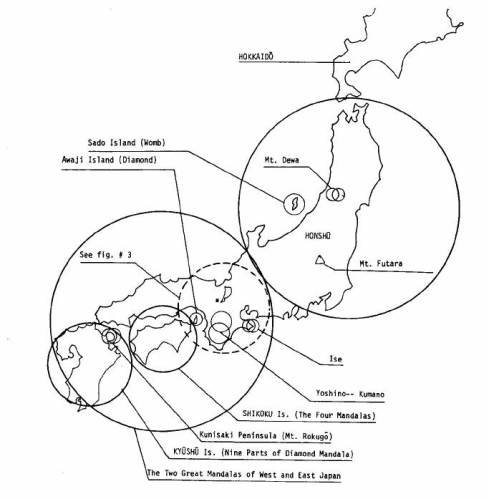

Such a projection whereby each summit of the Ōmine range is matched to a deity in the mandalas seems unique to Japan. The tradition has not endured, even though it is still remembered, as attested by confirmed Shugendō practitioner Nakai Kyōzen[4] during an interview conducted in 2008: “ I do not know at what point the mountains were given buddhas' names but from then on buddhas were venerated there. To this day, one is aware of entering a mandala – that is so for me, at any rate – and that is what I explain to practitioners”. Mountains represent a special space, close to the gods and the buddhas, where it is possible to re-ground oneself in the strongest meaning of the word by experiencing in one's own body the fundamental identity between the human world and the entire cosmos. This particular way of interweaving abstraction and materiality allows for endless combinations. It is also amenable to a transposition on a national scale: several 13th-14th century texts thus project the dual mandala on the whole of Japan in order to stress not only the depth but also the quintessence of the link that binds the country to Buddhism.

A l'époque médiévale, ce type de représentations s'inscrit dans un discours cherchant à positionner le Japon face à l'Inde et à la Chine. Historiquement, le Japon est le dernier des trois pays à avoir reçu la transmission du bouddhisme. Géographiquement, il est situé aux confins du monde bouddhique. Faire du Japon tout entier le Double mandala permet de contourner et même de retourner cette hiérarchie négative implicite, en utilisant l'axiome fondamental du bouddhisme ésotérique selon lequel le tout est l'un, et l'un est le tout. Qu'il s'agisse de représentations picturales ou de projections sur le paysage, les mandalas sont ainsi avant toute chose un appel à la prise de conscience du principe fondamental du bouddhisme ésotérique, qui correspond à une « transcendance dans l'immanence » selon une expression du bouddhologue Robert Heinemann[5] . La quête d'une atteinte de la bouddhéité dans ce corps-même en est l'expression la plus absolue, et les mandalas japonais à échelle du paysage entier permettent aux pratiquants de réaliser cet exercice en grandeur nature.

In mediaeval times, this type of representations related to a discourse on the position of Japan with respect to India and China. Historically, Japan was the last country to have received the transmission of Buddhism. Geographically it was situated on the fringes of the Buddhist world. Turning the whole of Japan into the Mandala of the Two Worlds was a way around, indeed a reversal of this implicitly negative hierarchy, through the use of the key axiom of esoteric Buddhism according to which “all is one and each one is all”. Whether through pictorial representation or projections onto the landscape, mandalas are thus first and foremost an invitation to be alert to the fundamental principle of esoteric Buddhism corresponding to “transcendence in immanence” as Buddhologist Robert Heinemann[5] puts it. The quest for the realisation of Buddhahood in this very body is its utmost expression and Japanese mandalas scaled to a whole landscape enable present and past practitioners to conduct this exercise live