What is the Nahda or awakening of the Arab world to modernity?

the 19th century progressed, the Ottoman Empire, under European pressure, was pushed to modernise its social and political structures. In the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Middle East, changes of diverse nature were effected, in the political, literary, artistic, social and religious realms. The notion of “awakening” – Nahdain Arabic – came to embrace all aspects of the struggle towards dragging Arab society out of the “stagnation” (inhitat) that had stalled it. The Nahda[1] was thus supposed to herald a new era marked with reforms and perforce in breach with a past deemed obscurantist and unjust (zulm), or at the least ossified (djumud). In this sense, the Nahda refers to a change-driven process rather than a specific event, and it will be easily grasped that its nature may have varied according to the social, political and geographic background of its actors. Accordingly it makes sense to outline some positions rather than establish a date or a punctual historical event.

With a view to clarify the phenomenon, historiography generally breaks it down into three main strands of cultural, political and religious Nahda. In cultural terms, historians and literature specialists often highlight as a founding factor of the Nahda the modernization of Arabic, which set in in the second half of the 19th century within the Levant's Christian communities and beyond. Indeed new, modern-sounding literary forms such as the short story (qissa) and the novel (riwaya) emerged, though writers did not for all that neglect the rehabilitation of the qasida, a poetic form used by pre-Islamic Arab poets. For journalists and press professionals, the revolution led by the Young Turks[2] in 1908, which put paid to the suspension of the 1876 constitution and reopened Parliament is considered as the beginning of the Nahda for all but Egypt where the framework for free speech had been much more liberal for a generation.

For the political actors who contributed to the devising of modern governmental structures, the Nahda was shaped by the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the struggles against European powers. Its most significant episodes are as follows: the 1916 Arab Revolt [doc 9] led by Hussein, Sharif of Mecca[3]; the 1919 revolution in Egypt that aimed to put an end to the “veiled” British protectorate established in 1882 and formally imposed in 1914; the fight taken to the French in 1919-1920 by one of Sharif Hussein's sons who, from Damascus, proclaimed an Arab Kingdom of Syria; The 1920 revolt in Irak, led by a coalition of Sunni, Shia and Christian religious authorities from Baghdad and the South of the country with a view to put an end to British occupation; The Druze revolt against the French in mandatory Syria in the mid-twenties. All these events were perceived as the very expression a national Nahda, synonymous here with independence.

In these political and cultural domains, the Nahda broadly operated independently from the actors' confessional origin. The journalists promoting a cultural Nahda were Christians, Jews, Muslims, as were its nationalist political actors. The third strand of the Nahda however was defined by religious obedience. In effect, in Christian and Jewish communities, the Nahda maintained close ties with the West through the schools set up respectively by the French, the British and the Americans as well as the Alliance israélite universelle and the Anglo-Jewish Association. They introduced an ever-growing number of students, some of them Muslims, to the sciences, the practice of European modern languages and a modern religious education. In education setups specifically reserved to Muslims, though there be links with the West, the influence it exerted was of a wholly different nature, in that there was a strong awareness that some selection had to establish what was and what was not acceptable “in Islam”.

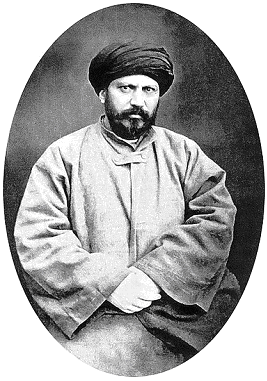

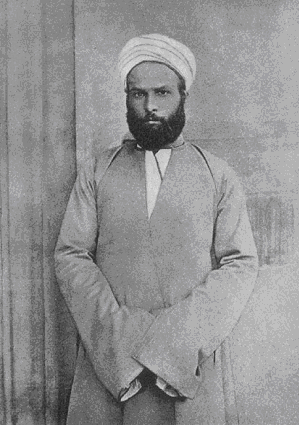

This paper, addressing this third and last aspect of the Nahda known as “Islamic Reformism” aims to grasp the issues at stake in the relation Muslim scholars kept with the concept of “science” around the turn of the 20th century. It focuses on three ulama who left their mark on the Arab Middle-East: Sayyid Jamāl Al-Dīn Al- Afghâni[4], Muḥammad 'Abduh[5], Muhammad Rashid Rida[6]. Upon arriving in Egypt in 1871, Al-Afghâni met Muhammad ‘Abduh, a student at the university of Al-Azhar[7] with whom he worked without that institution. Both felt certain that the Umma was set to decline should Islam fail to reignite from within; accordingly they proceeded to an in depth re-examination of the relation to the foundations of the Muslim faith. They condemned what they called blind imitation (taqlid) and advocated the use of reason and personal interpretation, Ijtihad[8]. They considered that any person with a command of Arabic and sound of mind was able to grasp the Koran, understood as the word of God and the Sunnah that summarizes the “actions” and “sayings” ascribed to Muhammad. These theses earned them the title – widespread but disputed among Orientalists and beyond – of “Protestant Muslims” on the basis of the analogy between Afghani and Luther's[9] approach towards a return to the origins beyond a part of the traditional corpus.

According to their reading of history, the early Muslim caliphs of the 7th century may well have, on the strength of their faith, encouraged the Muslim community to develop science, described as noble, and to practice Ijtihad, a method which in turn contributed much to the development of the sciences in the Abbasid[10] period. They went on to assert that the “faith” would have later weakened and division among Muslims grown causing the decline of the Muslim-lead part of the world. They concluded from this that in order to survive and regenerate, Muslims should act in the “spirit of Nahda” the instruments of which can only be found in an original, pure, reasoned and federating Islam. All ulama, preachers and imams on earth were thus called to preach the spirit of unity of the “Muslim nation” (Umma) by following the example of “pious ancestors” (salaf). Hence these ulama are considered the founders of Salafism[11].