Reception and support policies: The case of Switzerland

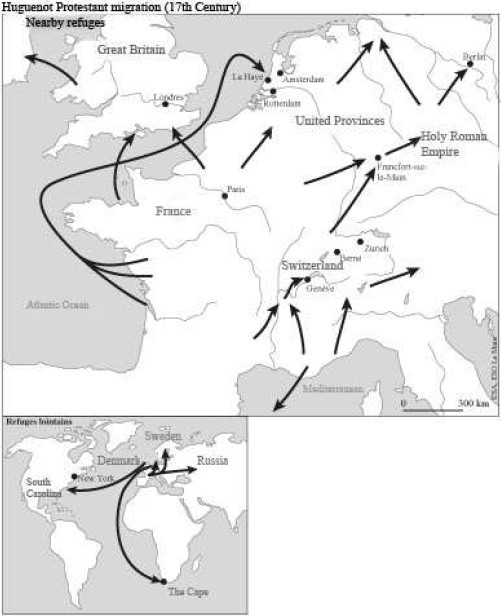

People from the Lorraine and the North of France generally passed straight into Germany whereas the fugitives from the South would most frequently pass through Switzerland. If we are to go by the numbers transiting via Frankfurt they are the larger group. This is hardly a surprise : the South of France numbered around 487,000 Protestants in 1670, against 174,000 in the North and 195,000 in the West (M. Magdelaine's estimations). Switzerland was a confederacy whose cantons were divided along faith lines between Catholics and Protestants since the 16th century. Its leaders had signed a treaty of perpetual peace with France in the aftermath of the battle of Marignano (1515) and had renewed it with Louis XIV[1]. Now Huguenots began to drift in during the 1660s. This was a cause for concern for the Protestant cantons for, since the annexation of the (once Spanish controlled) Pays de Gex and the Franche-Comté in 1674, there was no longer a major power to stand between the Confederation and Louis's kingdom. This was the more worrying since in 1681, France annexed Strasburg, a city allied to Bern and Zurich. This was the reason why the Swiss asked the jurists of Basel University whether they could accept the refugees on grounds of creed whereas a clause of the peace treaty specifically addressed the extradition of French fugitives on Swiss territory. In full view of the cannons of the ominously close French citadel at Huningue, the Basel jurists answered that the treaty clause did in no way apply to refugees on grounds of creed and that they may be received.

Most of the refugees who transited through Switzerland passed through Lausanne, Bern and Zurich, a smaller number through Geneva and Neuchâtel. The number filtering through Neuchâtel would grow as years went by : it should be noted that this principality was ruled by the Longueville house, the French Catholic rulers of a protestant county. Early refugees might have feared the presence of a Catholic prince in Neuchâtel but experience showed that they need not have. As for Geneva, Calvin's city, it no longer enjoyed the position it once held : the encirclement it suffered from Savoy, sworn enemy of the Protestant Rome had passed to France who had in place a Resident[2] who exerted strong pressures on the local government and regularly kept the king informed of the flow of refugees. On top of that, the city was facing difficulties in maintaining its supply lines and experienced frequent food shortages. In spite of its awkward position, Geneva took in some 777 refugees in 1,684, 3352 in 1685 and 1,485 in 1686. As a rule, the refugees promptly made for the Vaudois territory, then in the hands of the Calvinist lords of Bern and where they were safe. Thence, they could head for Germany via Basel or Schaffhausen, the two gates to the Empire.

There never was any question of offering the refugees a place to settle anywhere in Switzerland. This was put down to demographics by the authorities : the towns and the countryside were then thought to be overpopulated. Add to the bad economic situation at the end of the 17th century the cramped space in a territory dotted about with lakes forests and mountains, the need to humour the Catholic cantons and to handle the pressures exerted by France on Geneva, and the country's position is easily understood. This did not stop some refugees from settling down either because they had contacts in place or because their trade was deemed useful or even because they managed to sidestep the law. Switzerland's major problem remained, as Myriam Yardeni stressed, to channel their flow and speed up their passage. The authorities would even fall back on relatively harsh measures, for instance in 1692 and 1698 when they called for their expulsion because of a subsistence crisis : a policy of expulsion was decided upon in 1693 at the Diet of Baden and it took effect in 1699. Many refugees continued to stream in all the same. Throughout the Refuge, Bern's bailiffs provided their authorities with details of the transit through their territories and letters would be sent to their Neuchâtel neighbours asking them to take in more refugees so as to relieve this or that area in the cantons of Bern or Vaud overpopulated at that point in time. But the reverse also applied as Neuchâtel often reckoned it did more than could be expected.

The number of refugees rose so steeply during the 1680s that the Swiss confederates created a relief fund with a cost allocation base for shelter which would have to be adjusted several times. The accepted estimation is of 140,000 refugees supported between the years 1660 and 1770, bookending the Refuge. But this figure is outdated ; it goes back to the 19th century. To achieve a comprehensive view, the archives of every Swiss town and village would have to be checked through, which has never been undertaken. Some more precise local figures are known as a result of systematic research undertaken for some regions in the 1980s. Such is the case of Neuchâtel studied by Rémy Scheurer : from 1661 (when the first refugees arrived) to 1682 the figure is never higher than a few dozens. In 1683, it suddenly jumps to 200. In 1684, it has reached 385 and climbs steadily to 967 in 1685, over 1,300 in 1686 and finally 4,000 in 1687, between 1684 and 1691 Neuchâtel, a city of 3,500 inhabitants, took in its walls 18,000 refugees all told. By comparison, the city of Zurich, the “vorort” presiding over the Protestant cantons, gave shelter to some 20,000 refugees between 1687 and 1692 against its 7 to 8,000 inhabitants. At Schaffhausen, the number of refugees supported between 1683 and 1692 is of about 26,500, that is an average of 4,000 refugees a year for a population of some 5 to 6,000. Now, small villages must also be taken into account when there are available records. For instance Dombresson in the principality of Neuchâtel would give shelter to 6,000 thousand refugees between 1680 and 1715 whilst numbering only 348 inhabitants of its own in 1712 ! The exact count of refugees is an extremely difficult exercise that should take into account each and every Swiss Protestant locality while taking care not to record the same person twice.

Refugees mostly arrived bereft of all possessions. Upon reporting in a town, they often received a passade[3], granted by the authorities. While some might have left with some small sum of money, they had frequently spent it to provide for themselves or pay a smuggler – not to mention those who had been robbed on the way by brigands or soldiers while yet others arrive tired, sick or wounded. In Avenche, a French speaking city, under Bern's jurisdiction, expenditures for the hospital's destitute rose from 400 florin in the early 1670s to 1,600 in 1694 for a population of 1,000, which is a tidy sum. With emergency funds frequently out of cash, appeals were made for donations : The tradition in Neuchâtel to present envelopes for the collection of money for the refugees at the end of the service can be traced to these times. To this local fundraising must be added those undertaken in other reformed countries, such as the extraordinary appeal conducted throughout Europe in 1703 after Louis XIV had annexed the Principality of Orange and expelled the Protestants. Yet the Swiss also give money abroad (often in Germany) especially for the building of churches. The Swiss effort is particularly significant in those years of scarcity : for instance in Bern, 300,000 pounds were allocated to the refugees, that is 20% of the town and its territories' income in 1691. Fearful of yet darker days to come, the Swiss took pre-emptive steps, so that between 1690 and 1711 the city of Le Locle, in the principality of Neuchâtel aiding 4,000 refugees still made sure it did not hand out the full amount collected for fear of an eventual slackening in private giving.

The refugees' integration process varied, depending to some extent on trade and economic success (e.g. Suchard[4]), even if its impact has not yet been fully measured as its knowledge hangs on the pioneering studies of researchers such as Walter Bodmer. For peasant farmers, things were difficult : they could not take their property with them and hardly had the means to acquire some more. They were the first to set off further afield, which was not the case for craftsmen, for whom settling down was easier. In the event, it is in innovative, little exploited fields that professional establishment proved possible. This is the case for banking, which no doubt benefitted from Europe-wide networks of correspondents provided by the Protestant Diaspora. And it also applies to high value-added products in the textile (silks, indienne[5] etc...) and clock-making industries. With this, French high living was introduced in a more abstemious Calvinist Switzerland leading a good number of theologians to fulminate at the appearance of luxury in Switzerland : see Bénédict Pictet[6] in Geneva or Jean-Frédéric Ostervald[7] in Neuchâtel. There are not infrequent records of the authorities protesting some French Protestants' disregard for dress prescriptions (too colourful, sword-carrying etc...).

During the first decades, the temptation to play the identity card was overwhelming : thus in Lausanne one party in a court case asked for the case to be judged according to the law of their original province. This trend, comforted by the “associative” nature of the Ancien Régime, finds an expression in the creation in Switzerland of many French temples for the sole use of the Huguenots, for instance in Basel, Aarau, Zurich, Saint-Gall, Schaffhausen or Winterthur. Likewise, the refugees created their own charities to help their coreligionists, for instance in Geneva and Lausanne, where the refugees founded the “Bourse française”, a kind of associative corporation, a small local “Huguenot society”. Such institutions would disappear for the most part in the middle of the 19th century when historiography superseded Huguenot Memory. The disappearance of these institutions thus marks in its way the successful integration of the 20 to 22,000 refugees who settled in Switzerland.