Secular sovereignty underlain with religious sovereignty

There were English people settling in Ireland as early as 1170-71 under the rule of Henry II[1] Plantagenet. Its institutions point to English suspicions towards the island's native inhabitants. The chief of the executive was one Lord Deputy appointed by the king of England. Technically, he worked with a Council of Ireland of ill-defined powers that had, since the end of the 15th century, enforced policies decided by the privy Council[2] of England. Dublin did have a parliament constituted on lines similar to that of the English parliament. It was made up of an Upper House where the lords “spiritual and temporal” sat and a House of Commons where, at the end queen Elizabeth I[3]'s reign, about a hundred representatives met : 66 representing the 33 counties and 40 odd the cities and boroughs. The workings of this parliament brought out the tensions opposing the English to the Irish. In 1494 Poynings' law put an end to Irish autonomy. The Lord Deputy and the Council of Ireland must set before the Privy Council of England any bill the Irish parliament wishes to discuss. Once approved by the king of England and his parliament, the bill came before the Dublin parliament which could accept it, reject it altogether or amend it – but, in the latter case, it had to be sent back to London.

Thus, although they form the majority of the island's population, the Irish do not take part in the government of their country ; the English grant them charges only at local level. In 1541, on Henry VIII[4]'s initiative, the king of England assumed the title of king of Ireland in order to reassert his power before the church of Rome that claimed possession over the island it considered a papal fiefdom. This decision is to be read in the context of the conflict opposing Henry VIII to the pope ever since the English parliament voted in 1534 the Act of Supremacy that made the Tudor king « the only Supreme Head in Earth of the Church of England »

. The king would henceforward be able to repress “heresies”, appoint the bishops and organise the pastoral visits through which to correct “errors” and “abuses”. In other words the doctrine, the assessment of misguided opinions and the definition of the paths to “salvation” would from then on be the preserve of the political authority. Not even Constantine[5] or the Holy Emperor[6] had dared such measures.

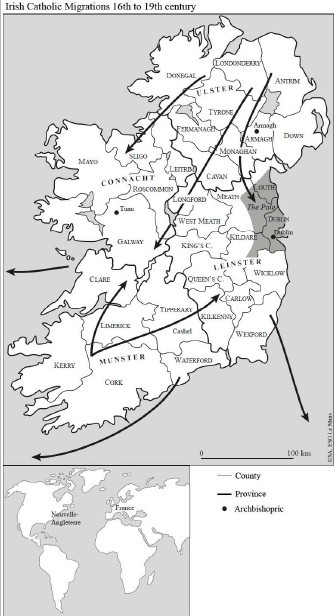

However, the English presence in Ireland remained discrete during the first half of the 16th century. English common law[7] was only applied in the Pale, that is the area stretching from Dublin to Dundalk. This was a small territory for some time protected by a fence (in Latin Palus) hence its name. Beyond this modest bridgehead, several regions held allegiance to the king of England, notably in the East and the South of the Island, such were the counties of Kildare, Ormond and Desmond.